We all wrestle with the concept of tempo from time to time. Does a given piece of music need to be fast or slow? Are we capturing the speed and character the composer had in mind when they wrote it? Where did the markings we see on our music come from and how should be interpret them?

What is tempo?

Fundamentally, tempo is the speed at which music is played. Every piece of music has an internal pulse holding it together – think of it like your own heartbeat. Sometimes a slow pulse is best (your resting heart rate while you’re sitting still, relaxing); at other times a quick pulse creates a sense of drive and excitement (just as your heart rate rises when you become more active).

So how do we know which speed of pulse is appropriate for any piece of music? Some composers are very explicit in their instructions, but often you need a little knowledge of musical history or be willing to do some detective work. Notation has changed a lot over the centuries, so an appropriate speed for the music of one period will be completely unsuited to repertoire from a different era.

Let’s take a look at how tempo has been notated through history and consider what this means for our own playing.

The Renaissance

Introducing the Tactus

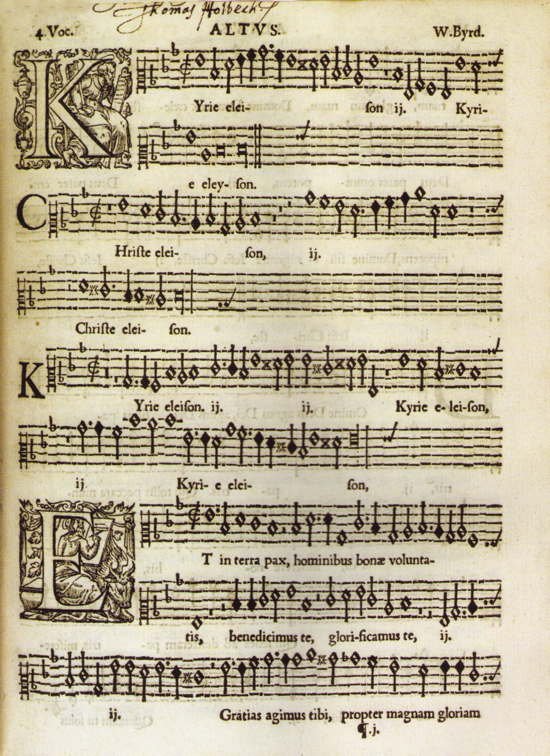

Without time signatures and barlines, the earliest forms of music used a different type of pulse to that indicated by a modern conductor. The rhythmic focus in Renaissance music was called the tactus - a unit of time indicated by the raising and lowering of the hand (to help the musicians keep good ensemble) and music began with a mensuration sign. This indicated how the tactus would be split, be it into two or three subdivisions. This tactus may have generally been close to the resting heart rate (a speed of which all humans have an awareness) perhaps 60 - 70 beats per minute, but historic sources aren’t consistent on this subject. Each tactus indicated the main beat (often a semibreve) which would be divided into either two or three minims, depending on the mensuration sign.

This is why much renaissance music is written in minim beats. To our modern eyes it often looks slower than other music, but to Renaissance eyes the type of notation helped indicate the tempo. As music became more complex the number of note values expanded to include smaller notes (our crotchets and quavers) to allow for faster music, but the tactus fundamentally remained the same. If you’re interested in learning more about the tactus and how it was used this video explains it very well:

So where does this leave us when we have to select a tempo for Renaissance music? The historic sources we can refer to are conflicting, so it often comes down to common sense and our own musicality. Here are some tips to help you:

Context

Look at the music and observe the types of note values it contains. Is it mostly semibreves and minims? If so, a semibreve pulse may be appropriate. On the other hand, if the music breaks down into smaller note values (crotchets and quavers) perhaps a minim pulse would be better.

Some music editors (particularly in older editions) try to be ‘helpful’ by halving the note values, turning minims into crotchets and so forth. For musicians who aren’t used to feeling a minim pulse this may be helpful, but the downside is the entire piece looks faster. Where once you had quavers you now have semiquavers. To inexperienced musicians that can look scarily fast, causing then to choose a pulse which is too slow to compensate. I know many musicians find counting in minim beats tricky, but it’s a skill you should persevere with learning because it opens up a vast array of music to you. Of course, if you ever choose to play from facsimiles of Renaissance publications reading minim (or even semibreve) beats is a must.

Below we have the same Byrd Fantasia in two different editions, The first uses Byrd’s own note values, while the second halves the note values to try and make it easier to read. Of course, this process also makes the music look quicker!

Vocal music

Do consider the text in the music you’re playing. Is it a cheery madrigal which demands a lively approach? Or perhaps it’s a melancholic love song where a slower tactus might be more appropriate? If you don’t speak the language used in the lyrics, set aside some time to Google the composer and title of the piece and find out what it’s all about.

Dance music

Here we have more clues to work with - the type of dance. A Pavan is a stately dance (although not necessarily very slow), while the Galliard is livelier, requiring the dancers to hop and leap in the air. I’m planning a future blog post looking at the different dance styles, but in the meantime the internet can once again be your friend. Most dances have a page on Wikipedia where you can learn more about the style and typical dance steps. This knowledge should inform your choice of tempo.

Switching between duple and triple time

Renaissance music often shifts between two and three time, but how do you know what to do with the tactus when this happens?

Look at many modern editions of Renaissance repertoire and you’ll often see a marking suggesting the length of the triple time bars should be equal to half a bar of the preceding time signature. This often creates a satisfying mathematical connection between the sections. If you refer back to treatises from the period you’ll find some recommend exactly this approach, while others advise making the whole bar length equal in both duple and triple time. One would hope there might be a clear notational way of showing which is correct in any given piece, but you’d be disappointed! This is one area where there was no notational consistency so my advice would be to try both and see which feels right to you. Sometimes the pragmatic approach is best…

Gabrieli Canzon Primi Toni, with an editorial suggestion regarding tempo relations at bar 44.

The Baroque

By the time we reach the Baroque period composers began adopting time signatures and bar lines consistently (there is inevitably an overlap with both being used around 1600), so the notation looks more familiar to our twenty first century eyes.

Use of language

Another new development was the use of language to indicate the tempo. Italian is the most common choice, but composers of other nationalities sometimes used their own language. It’s worth remembering that the Italian musical terms we’re familiar with today didn’t necessarily have the same meaning in the 17th and 18th centuries. For instance, in Romantic music Vivace is often interpreted as very fast, but for Baroque music it tends to imply a lively tempo - somewhere between quick and slow.

The concept of a unifying pulse hadn’t entirely disappeared and the term Tempo ordinario (often used by Handel) may well relate to a human’s normal walking pace. Other words used to describe tempo are intended to direct us to a speed relative to this consistent tactus, be it faster or slower.

Italian is not the only way…

Italian may have been the most common language for tempo indications, but it wasn’t universal. Many French composers used their own language and some of their terms are more expressive than their Italian counterparts - for instance Doucement (sweetly) and Gracieusement (graciously - as in the example by Hotteterre below).

Henry Purcell used Italian words in many of his works, but sometimes he used straightforward English words like Brisk and Slow, leaving the musician to figure out just how fast or slow that should be. In many of his Fantasias you’ll also find the word Drag written in places where he wishes to slow the tempo.

The influence of a time signature

Another way Baroque composers indicated the speed of a piece was through their choice of time signature. Explore the recorder sonatas of Telemann, for instance, and you’ll see that slow music is more likely to have a time signature where the lower number is a 2 - indicating a slow minim pulse. In contrast, music with a time signature where the lower number is 8 is generally played quickly. He uses both in his Recorder Sonata in C in exactly this way.

Telemann Sonata in C, 4th movement

Dance music

Dance forms were just as popular as during the Renaissance, although the dance types inevitably evolved over time. Here again, a little knowledge about the dance types should inform your understanding of the appropriate tempo, but bear in mind the composer may not have actually expected anyone to actually dance to the music if it appears as part of a sonata or concerto.

I saw a practical example of this many years ago at a competitive music festival where one of the set pieces was a Sonata in A minor by Schickhardt. The second movement is marked Allemanda and most of the competitors chose to play it at a swift tempo. This gave the music a breathless feel and many of the youngsters struggled with the semiquaver passagework. To illustrate a more appropriate tempo the adjudicator, Evelyn Nallen, got everyone on their feet and had us all dancing an Allemande together. The dance steps fall on the quavers beats so when we related this back to the Sonata, the music suddenly felt much more poised and playable. I think everyone there that day learnt an important lesson!

Schickhardt Sonata in A minor, 2nd movement

Harmonic tempo

In Baroque music one of the most important musical elements is the bassline. So much of the period’s music is led by the harmony, so if you only look at your own part you risk missing out on some crucial musical clues.

Take this Telemann Recorder Sonata, for instance, whose Cantabile marking suggests a singing style more than a tempo. Many players, when reading just the solo line, will select a very slow tempo, feeling a quaver beat, to make the faster notes easier. Now check the bassline and what do you notice? The majority of the harmonic movement falls in crotchet beats. Feeling a quaver beat means each bass note is very slow and it becomes almost impossible to retain a sense of pulse and movement in the continuo line. Instead, choosing a slow crotchet pulse (perhaps 54 beats per minute) allows the bassline to flow more easily, while the faster moving recorder part can still sing without being manically busy.

Telemann Sonata in C, 1st movement

This is just one example, but you’d be wise to consider all the musical elements before selecting your tempo. Harmonic tempo is a tool composers use in different ways to influence our understanding of the music. As we learnt when we explored the subject of hemiolas, these were often used as a means of speeding up the rate of harmonic change to flag up the ends of phrases. If you missed it, you’ll find that blog post here.

The Classical and Romantic

Beyond the Baroque, the recorder lost popularity and was largely ignored as a musical instrument until the early years of the 20th century. However, it’s worth taking a look at music of this period as it directly influences tempo markings in today’s repertoire.

Beethoven Symphony No.9

Perhaps the biggest development was the invention of the metronome by Johann Maelzel in 1815. This allowed composers complete clarity in their speed markings. One of the earliest adopters as Ludwig van Beethoven, whose first use of a metronome speed came in 1815 in his Cantata Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op.112. Beethoven’s fast tempi have inspired much debate over the years as to whether a disagreement between him and Maelzel resulted in the metronome’s inventor providing him with a faulty one. However, we also know from Beethoven’s own correspondence that he regularly had his metronome calibrated so it’s like he really did intend his fast speeds.

If you’re intending to play a piece which has a metronome mark I would treat that as something to aim for, but don’t be disheartened if the indicated speed is beyond you at first. If you have to opt for a more cautious speed initially and work up to it that’s absolutely fine. A musical performance which gets close to the composer’s metronome speed is always preferable to a scrappy, panic stricken interpretation which adheres slavishly to the marked tempo!

One trap I often see students falling into is when they look at the tempo markings which appear on many metronomes. For instance, yours might suggest that a marking of Allegro should be played somewhere between 120 and 168 beats per minute. Do remember the correct speed can vary enormously and the best pulse will depend on the type of rhythms and the notation. In my experience I’ve almost always found the markings on my metronome to be distinctly unhelpful and bearing no relation to the music I’m attempting to play, so I generally ignore them and follow my musical instincts instead!

Expressive use of language

Of course a metronome mark is only one part of the equation when it comes to showing a composer’s musical intentions. Speed is one thing, but as Romantic music became ever more expressive it was often necessary to give further information. Composers often augment their tempo words with additional terms to add a greater sense of expression. One of my favourites is Brahm’s instruction in his second Clarinet Sonata which marks the first movement as Allegro amabile - lively and friendly!

Brahms Clarinet Sonata Op.120 No.2

Some composers take these additional markings to extremes. In his 9th Symphony Gustav Mahler marks the second movement as Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers, etwas täppisch und sehr derb. If your German is as minimal as mine and you’re wondering what on earth that means, he intended it to be played as a slowish folkdance (like a Ländler), with some awkwardness and much vulgarity!

Tempo today

That brings us to music from the 20th and 21st centuries where, one could argue, we have the best of all worlds. With metronome marks and the ability to translate any language easily with modern technology, composers can typeset their music with ultimate clarity.

Paired with all the other possible expression marks (dynamics, phrasing, articulation etc) it’s easy to wonder how much autonomy we actually have as performers when composers specify so much detail. Should we ever deviate from those markings in the process of creating our own performance? Don’t forget we still have control over many aspects of our music making, including how flexible we are with the tempo - those little nuances of rubato which are unique to each of us. And some composers are still remarkably flexible about their creations. One composer I’ve worked with many times is very practical with her music and is often open to tweaks which might lead to a more fluid performance.

A composer’s prerogative to change their mind

Of course, composers can sometimes change their minds about what they’ve written. One example of this can be found in Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No.2. As well as being a composer, Rachmaninov was a superb performer and conductor and recorded this piece twice with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1924 and 1929. In his own performances you’ll find subtle changes to the tempi, notably accelerandi, which aren’t notated in the score. He also chose to shape the second musical theme in a way which isn’t shown in the score.

You could argue these are spontaneous and unimportant changes, especially as there was no way for recordings to be edited at the time. However, Rachmaninov also worked on the piece with Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra over a decade earlier and the conductor’s impeccably annotated scores concur with these changes.

These recordings are a fascinating glimpse into the mind of Rachmaninov the composer and performer and at least show us that no piece of music can be a rigid and unchanging entity. If only we had the chance to time travel in the same way and find out how composer/performers of earlier periods interpreted their own music!

So where does this leave us when we have to make our own decisions about the music we play? Ultimately I think we have to be practical and pragmatic. Yes, we should observe any instructions left by the composer, and if there are none we must be willing to find out what was expected via historical sources and online resources. Sometimes though decisions have to be made which allow us to create a musical performance.

There will be times when our own technical limitations stop us following a composer’s intentions to the letter. Does that mean we shouldn’t attempt to play that piece of music? I would argue absolutely not! The majority of musicians in the world are hobbyists, playing for their own enjoyment. Holding back from even trying a piece of music potentially deprives us of the opportunity to explore new music. Sometimes you need to have a go, even if that means playing the music slower or faster than the composer intended, knowing you’ll gain something from the experience, regardless of whether we’re ultimately capable of honing the notes to performance standard. Yes, do research the piece so you know what you should be doing, and then throw caution to the wind and enjoy the moment as a true amateur - someone who plays for the sheer love of music!