I’ve written about practising before, but always in a theoretical, didactic way - introducing you to the principles of practising. While conducting a recent orchestra rehearsal we encountered a passage containing some fast moving notes for most of the players. Naturally I encouraged them to practise these bars before our next rehearsal, but I also talked more specifically about how to practise them.

This topic has been uppermost in my mind of late as I’m working towards a concert myself. In one of the pieces we’re going to perform I have a couple of passages which stretch my technique and need some serious tidying before the concert. I’ve been working on this section each day and it occurred to me that you might find it interesting and useful to actually see and hear first hand what I do when I practise. So here we have The Practice Diaries - what may become the first in an occasional series. Using short video clips (most are 2-3 minutes long) I’ll take you along on the journey with me, explaining the process and hopefully you’ll see some progress along the way. The first few videos all come from one practice session, bringing you up to speed on the music I’m learning, plus some insights into what I’ve done so far.

Let’s jump into this warts and all exploration of my practice techniques. It won’t necessarily be pretty, but hopefully seeing my personal failings and successes may inspire you to make some of your own!

What are we practising?

The piece I’m focusing on here is Corelli’s Concerto Grosso Op.6 No.8 - often known as his Christmas Concerto. During the 18th century an alternative edition of it, with the solo violin parts transferred onto recorders, was published by John Walsh, with the advice that it could also be played as a trio sonata. That’s exactly what we’ll be doing - using two recorders, cello and harpsichord.

Day 1 - let’s get started…

Although this is Day 1, I’ve been practising the Corelli for a couple of weeks already, so let me explain my journey to this point. But before that, here’s one passage which particularly needs my attention - the semiquavers from bar 70 to 80. The image below is a snap of my own copy, complete with my pencil markings, which are intended to help me play it better.

Corelli Christmas Concerto, 4th movement - Adagio-Allegro.

Let’s begin with a brief introduction to the music and this new project…

Although I’ve played this piece before, I still need to asses how much work there is to be done, considering one or two small adjustments to make it feel more recorder-friendly…

The next step is to identify where I’m particularly prone to glitches and mistakes. I mark these in my music as a warning, reminding me that I need to concentrate even more in these spots.

Next I explain the way we learn when we practise and what goes on inside our bodies to make sure the work we’ve done stays done!

I wrote another blog post about this topic last year and if you haven’t already read it, I strongly suggest you do. When I learnt all about the magic of myelin it was a real game changer for me - you can read all about it in my blog post here. In these early stages, practising slowly is the best thing you can do, ensuring you’re not learning mistakes into the music.

Do you love your metronome? I love mine!

Used in the right way it can be a fantastic tool, especially when you want to gradually increase the speed of a piece of music. Here I talk about the way I use a metronome when I’m practising.

If you want more metronome top tips why not take a look at my blog post all about this brilliant and much maligned tool?

But how does a metronome help you increase the speed of the music? I have a cunning plan which, with a little patience and persistence, is utterly foolproof - watch it in action here…

Having explained my strategies for the early days of practising a difficult passage, let’s see if the work I did yesterday has stuck, and find out which bits still need some polishing…

If you feel you’re making good progress, a clever way to test this is by making the music even harder. Let’s take a look at my own strategies and how well they can work…

It’s very easy to get caught up in thinking about your fingers, forgetting about all the other things you need to consider at the same time! Here I talk you through some of these:

Have you ever tried practising the music backwards? I did just that and discovered that it can be another really useful strategy!

How long should we practise for and how often? Here I ponder the ins and outs of practice routines. You might be surprised how much you can achieve in a modest amount of time if you practise in the right way.

In today’s practice session I realised that hidden dangers occur when familiar patterns change…

My final snippet from today’s practice session - let’s see how much progress I’ve made…

Now it’s time to go and do some different work - I’ll return in a few days with some more updates and glimpses behind the scenes, warts and all!

Day 2 - more thoughts on alternative fingerings, relaxation and when to feel you’ve really fixed a problem

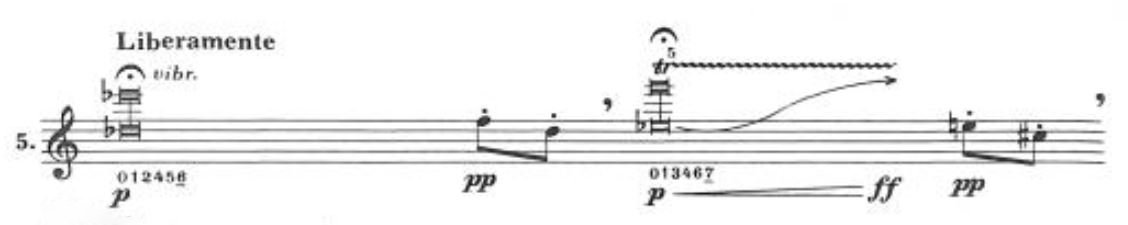

After a good night’s sleep I’m back on the case, now turning my attention to a different section of the music, shown in the image below. Once again you can see I’ve marked the groups of notes which need my attention.

Corelli Christmas Concerto, 6th movement - Allegro

I started this project to help you with your practice, but looking back at the previous day’s clips I realised they had their uses for me too!

At what point can you say you’ve really mastered a passage? I consider this today and find out if I can put my own advice into practice…

My final thought for today - using smooth or detached articulation.

Day 7 - getting to grips with slurs and changing gear

Five days have passed since I last spoke to you, but I’ve been practising every day, making incremental improvements. Each day new ideas occur to me, so let me explain some of my latest discoveries with you…

We’ll start off by thinking about how I can control the movement of my fingers more effectively while I’m playing slurs.

There comes a point, when practising with a metronome, that a gear change is required. As I’ve gradually increased my speed that moment has arrived - here I talk you through my thought processes on this.

Here we have a fresh scan of my music. Over the days I’ve gradually added a few more markings, to help remind me what I need to think about and where. These include updates on where my metronome practice has got to, and notes about the specific fingers I need to work more efficiently as I play.

My final thought for the day is when you should stop practising. Concentration is a finite resource - knowing when your allocation for the day has run out will help you practise more efficiently and effectively!

Day 12 - playing with other people and trying to overachieve

After a weekend off and a rehearsal with my colleagues I have a much clearer perspective on how successful my practice has been so far…

Playing the music at the right speed is one thing, but it pays to build in a margin for error. Here I look at my aims for the remaining few days before our concert.

Finally, I consider the possibility of making mistakes during the concert - after all, no one is perfect!

The final countdown…

As I publish this post, we have six days left until our concert, but will I be ready for whatever a live performance can throw at me?

I’ve practised in a thoughtful way, taking small steps to work on my weak areas. At no point have I spent more than an hour a day on my practice, but instead I’ve focused the bulk of my attention on the passages that need the most work.

What about the rest of the concert programme?

Alongside the Christmas Concerto I’ve spent shorter periods tidying up the other pieces. It’s rare to perform an entirely new programme in any concert, so many of the other works are ones I’ve played before and know well. I keep these ticking along in parallel with the Corelli, but the good quality practice I’ve done one them in preparation for previous concerts means they don’t need the same quantity of work.

Have you enjoyed this glimpse behind the scenes?

Practice can seem like a dark art. People talk about it a lot, but how often do you get to see and hear exactly how a professional practises?

I hope this look behind the scenes has given you some inspiration for your own practice sessions. Please bear in mind I’m coming to this work as someone who’s spent many years studying; developing my technique and musicianship. Some of the music I find easy may seem like an impossibility for you at the moment, especially if you’re still near the beginning of your recorder journey - please don’t let that put you off. All of the techniques I’ve talked about and demonstrated in these video clips can be modified and used in your own practice sessions. Your tempi may be slower, and your pace of improvement may be more modest, but I absolutely believe that anyone can become a better musician and technician if they practise in the right way.

If you’ve found this video diary helpful, please do let me know by leaving a comment below. Is this something you’d like to see more of? If so, are there specific topics or techniques you’d like help with? I have lots of ideas, but they’ll be so much more meaningful if I know what you’d like help with.