One request I’ve received several times is for a blog about this topic, specifically aimed at those who play in or run recorder groups organised by individuals rather than large scale orchestras. Here in the UK, this often takes the form of a u3a group or a small ensemble which meets regularly in someone’s home. There are probably as many different types of ensemble as there are composers, so catering for every scenario is all but impossible. However, I have lots of practical advice to share, and I hope you’ll read through and make use of whichever points are helpful for your situation.

While researching this topic I sought out the thoughts of several recorder playing friends who run amateur groups in their own homes and local village halls. I see a huge array of ensembles as I travel around the country, but a single person can’t foresee every possible challenge. As I anticipated, my friends had lots of advice to offer in the light of their own experiences. Much of it I already had on my ‘must include’ list, but their thoughtful emails contained points I hadn’t considered too. This just goes to show that five heads are better than one, so I’d like to say a huge thank you to the folks I contacted - you know who you are!

Starting an ensemble

If you’re still at the planning stage, there are some things to consider before you even hold your first rehearsal. I don’t think there’s any need to cover each of these points at length - it’s more a checklist of things to consider.

Who are you intending to play with? Do you need to recruit players or perhaps you already have group of recorder buddies who are itching to get started? Word of mouth can be great way to find people, but your local music shop may know of other like-minded players too. If you’re a member of an SRP branch (or the equivalent in your country) don’t be afraid to ask if others would like to join you for some additional playing.

Where will you play? For a small group, someone’s living room may be sufficient, but if you’re planning a larger ensemble you may need to consider booking a room in a local hall or community centre. You’ll need good lighting, adequate ventilation (and heating for the winter months) and suitable seating for playing. If you’re hiring somewhere, do remember to check the chairs don’t have arms as these get in the way when playing the recorder!

How often do you intend to meet? You may prefer weekly, monthly or on a more spontaneous basis. Do discuss this with your members and agree whether everyone is expected to attend every session. You may prefer an informal arrangement where folk come along as and when they can. But this could be restrictive, especially if you wish to work on the same music for a period of time.

What are your aspirations for the group? Are you after fun or education? Maybe your aim is to simply explore unfamiliar music, or perhaps you want to really work at pieces to improve your musical and technical skills? It might be you even want to work towards a performance. I’ll talk about this possibility again later. The most important thing is to talk to the other musicians and make sure you have the same aspirations.

Do you have a good range of instruments? If you want to play a variety of music it’s helpful to have a mix of different sizes of recorder at your disposal. One of the pleasures of ensemble playing is being able to use different sizes of recorder, so it can be frustrating if one person gets stuck on the bass all the time. If your ensemble has lots of members who only play descant or treble this might present a good opportunity to convert some or all of them larger sizes of recorder. There are tutor books aimed at those who want to learn a new fingering but I’ve also written a blog about this topic which may be a useful starting point.

Sourcing music

One very important factor when running a recorder group of any kind is choosing the music you’ll play. Historically, printed sheet music was required - often bought from your local music shop. These days most small music shops are unlikely to stock a vast array of recorder consort music, but fortunately there are lots of other sources for music. Let’s look at the various options…

Printed music providers

The most comprehensive source of printed recorder music here in the UK is Recorder MusicMail. They stock a huge array of repertoire for any number of recorders, and if they don’t have what you’re after they can usually get hold of it. They stock publications from the big mainstream publishers (Schott, Universal Edition, Moeck, Faber etc) as well as pieces from the myriad of smaller publishing houses such as Hawthorns, May Hill Music and Willobie Press.

Recorder MusicMail offers an excellent mail order service, but this doesn’t allow you to browse the music and see what it actually looks like. For this it’s worth attending one of the large-scale recorder events (such as the SRP National Festival and some of the larger recorder courses) which take place annually where they often have a presence. Taking an hour to leaf through the boxes of music allows you to see the score and judge how hard the parts are.

I’ve focused on the supplier I use most often here in the UK, but I’m sure there are similar shops in many other countries. Please do share your recommendations in the comments below.

Free online editions

There are many websites offering free or low-cost digital editions of music – especially repertoire which is now out of copyright. These are some of the ones I use most. Do leave a comment below to share other sites you use to source music. Click on the titles in red to visit these music providers.

International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) - a huge outlet for music which is out of copyright for every possible instrument. You can search by composer, instrument, ensemble, title, musical period and more. There are masses of original and arranged pieces for recorders, and a huge array of other music (instrumental and choral) which is ripe for arrangement. You have to be prepared to dig around to find things if you don’t know the exact title you’re searching for, but I’ve discovered a multitude of gems here. If you have a particular number of parts you’re looking for (quartets for instance) a good starting point is to type 4 recorders into the search box. This will bring up a choice of original pieces or arrangements and you can browse from there. The website is free to use, albeit with a delay of a few seconds in loading some of the pieces for free users. For a small annual subscription (currently $32 a year or $3.49 per month) this delay is removed and you’ll have the warm feeling that you’re helping keep this amazing site going.

Choral Public Domain Library (CPDL) - a vast repository of vocal music, much of which will work very well on recorders as the human voice has a similar range to the recorder. There is a degree of overlap with IMSLP, but it’s worth exploring both sites.

Gardane.info - another large online library of music for recorders (some original and some arranged) run by Andrea Bornstein. To access this you need to register for a free account and you’re welcome to make a financial contribution to Andrea to help support the site if you wish.

My own website - (apologies for the shameless plug!) I’m sure the vast majority of people reading this will already have rooted through my consort downloads page, but if you’re new here and haven’t yet discovered it, do take a look. I share a new piece every two weeks (many of them my own arrangements, made specially for you). All are available to use free of charge, but I’m grateful to anyone who makes contribution towards my professional time and helps me keep the site running.

Arranging your own music.

If you’re up for creating your own arrangements there are endless pieces on the sites I’ve listed above which could be purloined for recorders. Many choral and viol consort pieces work with just a simple transcription - transferring each voice straight to the appropriate clef for recorders. More complex arrangements are possible too, but this may require a greater knowledge of music writing than you’re comfortable with.

If you want to make your own arrangements there’s no reason why you shouldn’t use a pen/pencil and manuscript paper - there are even lots of websites where you can download manuscript paper to print at home. If you prefer properly typeset music you can spend a lot of money on software such as the full versions of Sibelius and Dorico, but there are free options available too, such as Musescore, Sibelius First and Dorico SE. There’s a bit of a learning curve when you first begin typesetting music, but it’s a skill worth acquiring if you find yourself making lots of arrangements.

Selecting the right music for your group

Armed with knowledge about where you can source music, the next step is to find the right sort of music for your group - one size doesn’t fit all. If you have a well-matched ensemble, where everyone is pretty much at the same standard, this may be fairly straightforward. You might even be able to club together and ask the members to bring along their own music to share.

If you have a mix of abilities it can be trickier to keep everyone happy though…

When I find myself working with a mixed level group I aim for a standard that allows everyone to at least have a go at the music. I try to ensure less confident players have someone who’s more advanced alongside them to offer a helping hand and reassure them that perfection isn’t an absolute requirement.

With a larger group you may be able to work on repertoire which is slightly harder because the weaker players will be buoyed up by the stronger players around them. There’s a lot of satisfaction to be had from playing with musicians who are slightly more advanced than you as it helps you lift your own game. On the other hand, don’t be over-ambitious. Sometimes it pays to select something simple which you can play really well. This allows everyone more brain space to think about technique, good tone and tuning - not just survival!

How many parts?

Some of your members will no doubt be confident holding a line on their own, while others may need support. Try to be sensitive to this and offer help where it’s needed. If all your members are confident readers you may be able to have the same number of parts as players, but it’s always wise to have some smaller scale pieces handy in case a piece doesn’t work. Whenever I work with an unfamiliar ensemble I take along far more music than I expect to use. That way I always have some back up music in case the group romps through things quicker than expected, or need something a little less challenging.

What style of music?

Many recorder players feel most at home with repertoire from the Renaissance and Baroque periods – after all, it’s the music we play most often. Don’t overlook pieces from the last 100 years or arrangements of repertoire from the Classical and Romantic periods though. It’s always good to expand your musical horizons. Exploring different styles will stretch you musically and technically and will no doubt help you play everything better.

Why not theme your sessions?

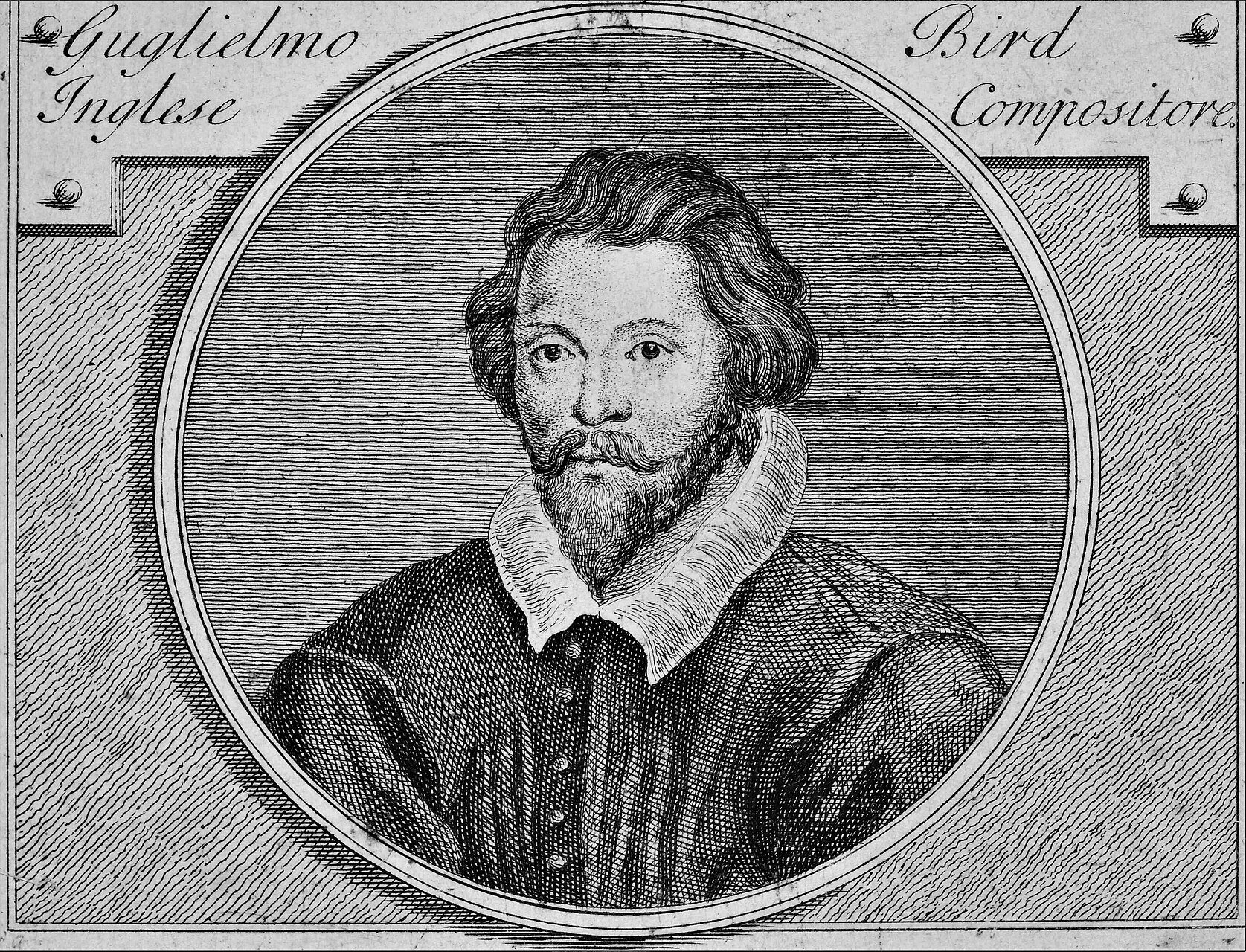

There’s no reason why you shouldn’t enjoy a variety of different music at your playing sessions – just as with food, a varied musical diet is no bad thing! However, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t theme your rehearsals too. You could do this by period (Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, jazz), musical form (dances, madrigals, fantasias) or by composer. This can help bring a focus to your sessions, allowing you to see the commonalities and differences between related pieces of music.

Ten more practical tips…

Get to know the music from the inside.

If you’re responsible for directing the group it pays to at least be able to play through the parts, so you know from personal experience where the danger spots occur. No one expects you to spend hours learning every part perfectly, but some practical experience will help you understand where the musicians are most likely to encounter difficulties.

Prepare the score