It’s a year or so since I last brought you one of my Sounding Pipes playlists, and during the intervening months I’ve been collecting a myriad of wonderful recordings, played on recorders of all sizes. This eighth edition of Sounding Pipes, focuses on one of our instrument’s superpowers - its infinite flexibility and versatility.

The recorder’s native repertoire stretches for 1000 years, but we do have a missing century and a half - that period from around 1750 to the early twentieth century when orchestras grew ever larger, thus squeezing our relatively quiet instrument into oblivion. During this period other woodwind instruments evolved, with a larger bore and extra keywork to give them added power, a greater range and the ability to easily play chromatic music. The recorder, however, missed out on these innovations and it wasn’t until well into the 20th century that modern makers really began to experiment and expand our instrument’s technical possibilities.

There were of course recorder-like instruments that persisted in particular geographic areas (as you’ll see and hear below), but even these remained fairly true to the way Baroque recorders were voiced. At first glance this lack of evolution may seem a negative thing, but I would argue it’s ultimately worked in our favour. Having too much choice can be a bad thing - one gets paralysed by the endless possibilities. Because we have that historical gap in our instrument’s native repertoire, recorder players have become very good at ‘borrowing’ music and making it our own. Admittedly it’s not possible for every type of music to suit the recorder (anyone fancy Wagner’s Ring Cycle of operas for voices and recorder orchestra?!), but our willingness to try playing unexpected music on recorders has proved surprisingly effective at times. It’s hard to think of another instrument which can play such a wide range of musical styles as effectively as the recorder. For instance, how often do you hear a string quartet playing jazz, or a clarinet choir exploring the medieval stylings of Perotin?

It’s this thought which inspired the collection of music I’ve brought together for you today. Prepare yourself for a smorgasbord of musical styles, from the Medieval to jazz, with forays into Classical opera and lush orchestral Romanticism along the way. I realise not everything will be to your tastes - after all, you can’t please all the people all the time. Hopefully though you may find some unexpected pleasures along the way and I feel sure it’ll broaden your horizons, opening your eyes to even more of the recorder’s possibilities.

Let’s begin by stepping back 700 years to Medieval France….

Guillaume de Machaut - Douce Dame Jolie

Performed by La Morra: Corina Marti (recorder), Michał Gondko (lute), VivaBiancaLuna Biffi (voice, vielle) and Marc Mauillon (voice).

This was one of the most popular songs from 14th century France and here it’s performed on instruments which would have been familiar at the time. Like most popular songs today, the lyrics are written in verses, interspersed with choruses, talking of love - some things remains the same, even after 700 years!

Sweet, lovely lady for God's sake do not think that any has sovereignty over my heart, but you alone.

For always, without treachery cherished have I you, and humbly all the days of my life served without base thoughts. Alas, I am left begging for hope and relief; for my joy is at its end without your compassion.

Sweet, lovely lady....

But your sweet mastery masters my heart so harshly, tormenting it and binding In unbearable love, so that [my heart] desires nothing but to be in your power. And still, your own heart renders it no relief.

Sweet, lovely lady....

And since my malady healed will never be without you, sweet enemy, who takes delight in my torment with clasped hands I beseech your heart, that forgets me, that it mercifully kill me for too long have I languished.Sweet, lovely lady....

Hildegard of Bingen - O virtus sapientiae

Sophia Schambeck - double recorder

Much is made today of the need for women composers to be more visible - the world of composing has long been dominated by men. But there have always been women who defy this norm, composing music which survives to this day. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) is a prime example. A German Benedictine Abess, she was also a polymath, active as a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary and as a medical writer and practitioner during the Middle Ages. And she did all of this over a long life - 81 years - which would have been exceptional during the 11th century.

Music at this time was simple in form - single melodic lines, or perhaps organum - that’s two lines played in parallel, creating the simplest form of harmony. Here this beautiful melody, O virtus sapientiae, is performed by Sophia Schambeck on a double recorder. With one hand she plays the tune, while the other half of the instrument creates a static accompaniment of drone-like held notes. The result is absolutely mesmeric.

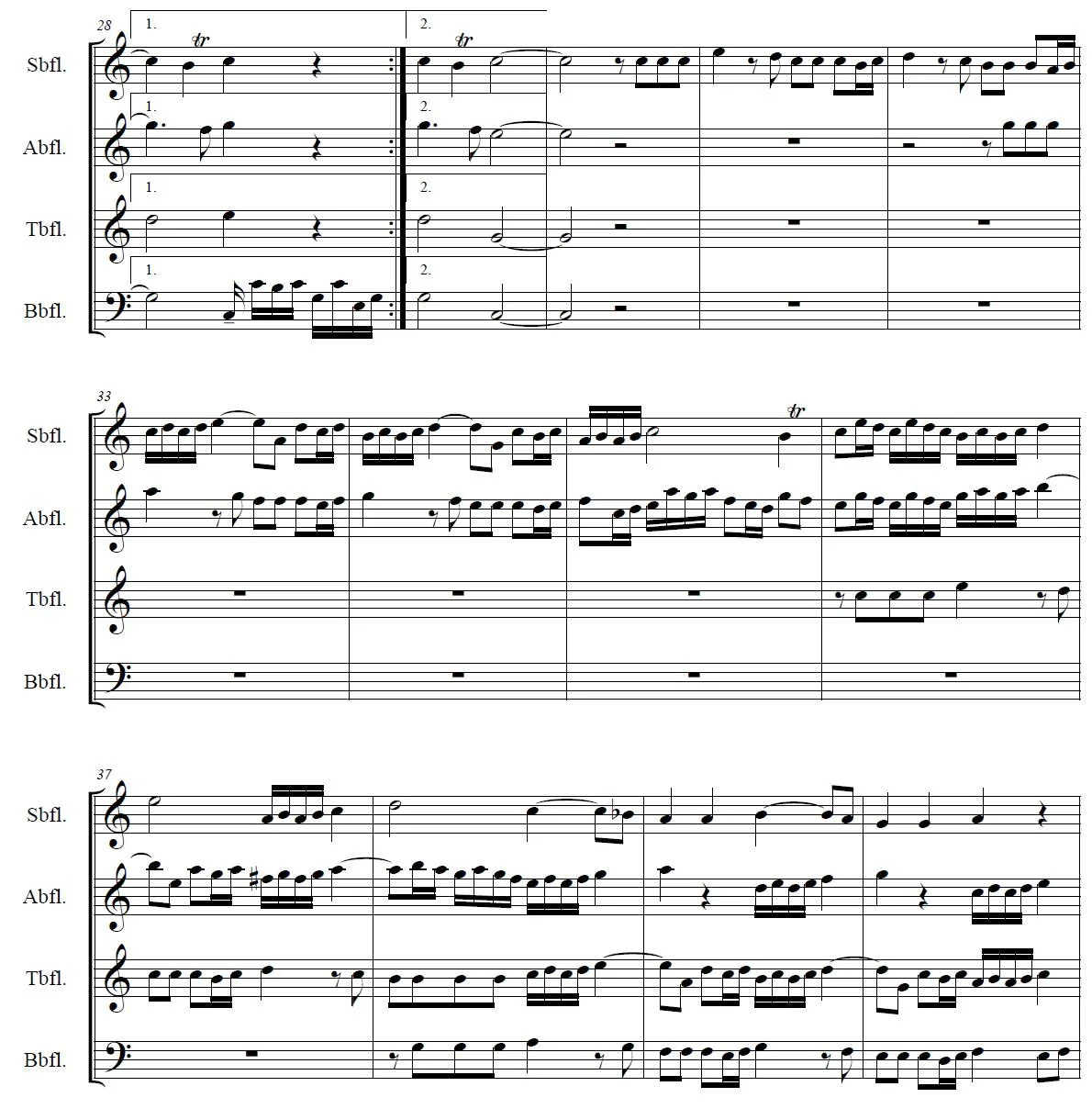

Antonio Vivaldi - Concerto RV580 for 4 recorders, first movement

Recorders: Michael Form, Claudius Kamp, Yi-Chang Liang, HyeonHo Jeon, Baroque Cello: Hyunkun Cho, Harpsichord: Eunji Lee

It’s been said that Antonio Vivaldi composed the same concerto 600 times, but I think that’s more than a little unfair! Granted, there are many works among his output which feel quite similar - hardly surprising for a composer who was so prodigious. But there are some wonderful works of tremendous ingenuity and drama too. This piece comes from a collection of twelve concertos for strings, published in Amsterdam in 1711, titled L’estro armonico - The Harmonic Inspiration. In this volume Vivaldi uses solo instruments in a creative way, with combinations of soloists rather than just a single violinist. In this concerto, No.10, he writes no fewer than four solo violin parts and in this performance they’ve been replaced by four recorders.

One of the challenges of playing music with multiple recorders of the same size is making each voice stand out as an individual. Without the dynamic range of the violin, recorder players have to get creative with articulation instead, using infinitely varied note lengths to create contrast between the lines. This wonderful performance does so beautifully when all four recorders are together, as well as having solo spots featuring each individual player.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Overture to The Marriage of Figaro

Flutes in Situ - Belgian duo Laterna Magica: Nathalie Houtman & Laura Pok - csakans, Thomas Waelbroek - piano.

From the Baroque period, we shift forward into the recorder’s missing century and a composer who wrote some of the most exquisitely perfect music - sadly none of it for our instrument. As I mentioned earlier, recorder-like instruments continued to exist in small pockets throughout the Classical period. One of these was the csakan in Austria and Hungary. Like the recorder, it’s a fipple flute, but usually pitched in A flat and designed as part of a gentleman’s walking stick. A small group of composers (Anton Heberle and Ernst Krähmer being the best known) wrote original music for the instrument, but it wasn’t unusual for performers to use it to play arrangements of popular music from the era.

In this arrangement of the Overture from The Marriage of Figaro, Nathalie Houtman and Laura Pok play two csakans, accompanied by a piano typical of the period. The lighter sound of the piano (compared to modern grand pianos) pairs with the csakans perfectly and it’s such a delight to hear Mozart played in this way.

Gustav Mahler - Symphony No.1, third movement

Hsin-Chu Recorder Orchestra, conducted by Meng-Heng Chen

Mahler isn’t a composer who immediately springs to mind when you think of the recorder, but this is an unexpected arrangement which works surprisingly well. In the third movement of his first Symphony Mahler reuses the familiar children’s song, Frère Jacques, changing the key from major to minor to create a funeral march. Along the way he also incorporates melodies reminiscent of Czech folk songs. Mahler was a master of orchestration, using colourful combinations of instruments, and that’s the one element which inevitably remains absent in a recorder arrangement. The Hsin-Chu Recorder Orchestra add cello and double bass in their performance, and the pizzicato strings sound undoubtedly adds a fresh tone colour. Even if you disagree with the borrowing of music which is so alien to the recorder, I think it’s important to push the boundaries from time to time to explore the almost limitless boundaries of our instrument.

Eugene Magalif - Colibri

Berlin Recorder Orchestra, conducted by Simon Borutzki

Born in Belarus and now living in the USA, Eugene Magalif may be an unfamiliar name, but he has a long track record of composing music for the flute. Colibri (Hummingbird) was originally composed for flute and string orchestra and was crucial in bringing Eugene to the attention of flautist James Galway, with whom he had a long working relationship. Simon Borutzki, the conductor of the Berlin Recorder Orchestra, created this arrangement for recorder orchestra and, listening to this spectacular performance, you’d be hard pushed it realise it’s been borrowed - it first the BRO like a glove.

Eugene writes the following about the piece:

“Hummingbirds migrate annually from Central America to New Jersey for the summer months and then back again, flying thousands of miles. They are the only birds that can move in any direction and hover in the air like bees. There is a family of hummingbirds that return every summer to our backyard, where we put out feeders filled with sweet nectar for them. One day I was sitting on the balcony, talking with professor Oleg Sytianko, from Turku, Finland. He asked me to write something for flute, promising to perform it at the music conservatory. In the same moment, the hummingbirds arrived. Seeing these cheerful little birds, a melody instantly came to mind—a simple melody, but with a special rhythmic pattern.”

Chick Corea - Armando’s Rhumba

Arrangement by Tal Zilber. performed by Tali Rubinstein - recorder and Tal Zilber - piano

My last Score Lines blog introduced you to advice from jazz musician Chick Corea, so when I discovered this phenomenal performance of his music by Tali Rubinstein I just had to include it in my Sounding Pipes playlist. This may have the genes of jazz at its heart, but Tal Zilber also manages to squeeze in snippets of music from Georges Bizet’s Carmen and J.S.Bach’s Badinerie from his second orchestral suite. A musical tour de force!

That concludes my playlist, featuring a tremendous variety of music, covering ten centuries. I can’t think of another instrument which could so effortlessly play all these different styles of music and I hope you’ll agree our lives as recorder players are richer for this. Have I missed out a style of music you might have included? If so, why not leave a comment below and share some of your favourite recorder gems with us?