We like to think we’re all unique individuals, tackling life in our own special way. But anyone’s who’s worked as a teacher knows this is only partly true. Yes, everyone has a different character, but when faced with a class of pupils you quickly learn there are mistakes that everyone makes.

Photo by Dayne Topkin

I spend much of my working life coaching groups of adult musicians and, while each ensemble is unique, I find myself offering certain key pieces of advice to every one. Many of of you will be familiar with Walter Bergmann’s Golden Rules for Recorder Players - if you’ve been following the Score Lines blog for a while you’ll probably seen them in my first post, back in September 2021. While his advice is encased in pithy sayings I feel absolutely sure each one is founded upon an experience Walter Bergmann had while coaching amateur musicians.

Several people have suggested I share some of my own ‘Golden Rules’ here, so over the last few months I gradually jotted things down as they occurred to me. Now I can’t promise to be as witty as Dr Bergmann, but I can promise you’ll find yourself nodding in recognition at some of them as you glimpse your own bad habits. No doubt others will occur to me as soon as I press ‘publish’, so this may yet become the first in an series of blogs, but for now I hope you may be able to use some of these brief pieces of advice to avoid some of the mistakes we all make from time to time.

My collection of jotted thoughts fall roughly into two categories :

Aspects of musical notation and how we interact with it

Thoughts about playing style and ways to improve one’s performances.

With that in mind we’ll tackle them in that order.

Useful nuggets of notational advice….

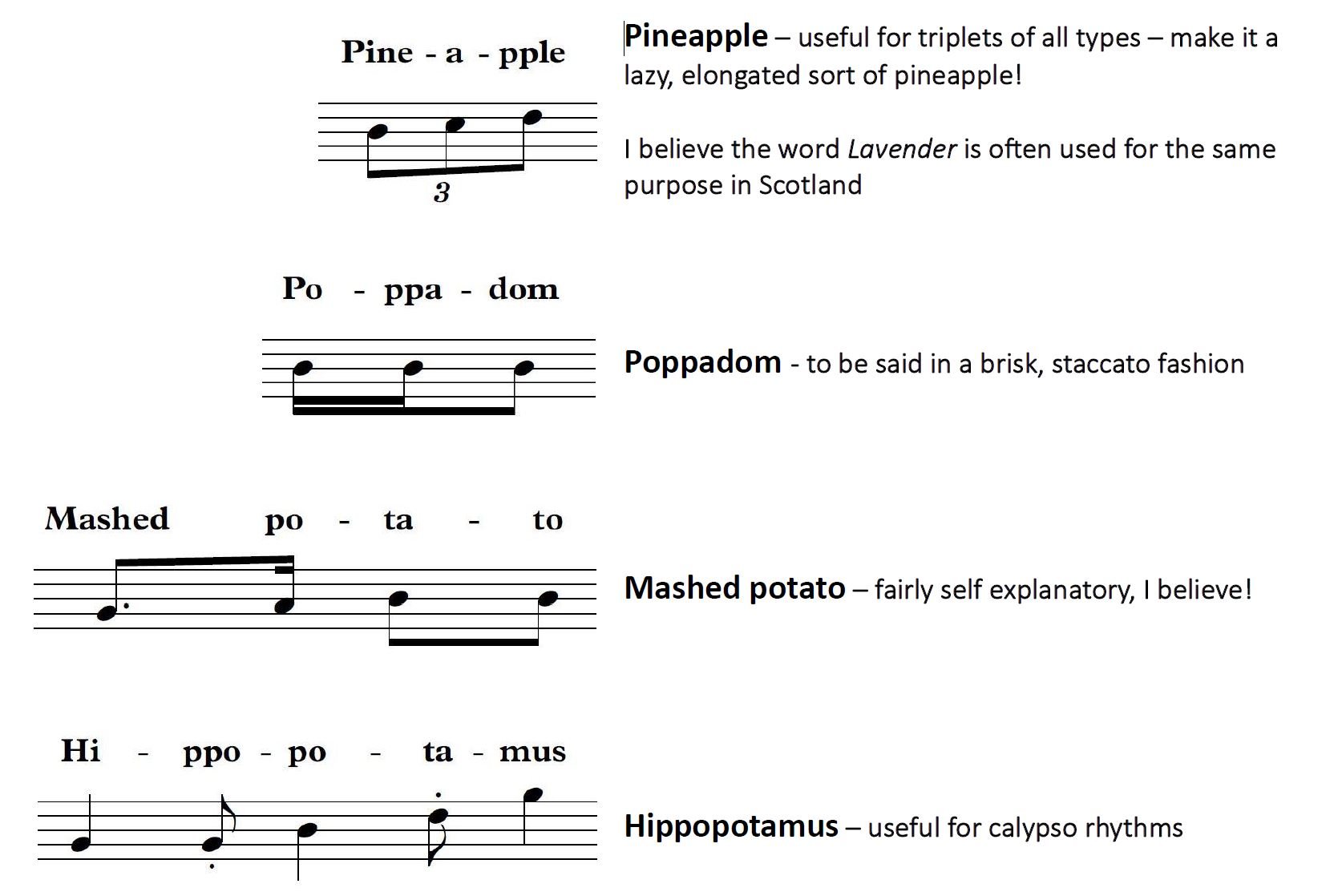

Using language to help with rhythms

Some people find it very natural to translate rhythm on the page into sound, while others need a helping hand. It often pays to think of rhythms like multi-syllable words, rather than taking each note on its own, and words can help you remember the way these groups of notes work together. For some reason many of my phrases have a culinary feel. Quite what that says about me and my relationship to food is debatable, but it works for me! Here are some of my favourites, but don’t be afraid to come up with your own too.

Rests as silent notes

It’s easy to view rests in music as an absence of sound - a sort of musical black hole from which light, sound and matter cannot escape. I would argue a better approach is to consider them simply as silent notes. Play or sing through the following phrase and consider where the rests occur.

If you consider the rests as holes in the music, it’s tricky to know where to place the next note. But if you feel them as a silent notes - one which has shape and mass, but no sound - it’s easier to use them as a springboard for the notes that follow. Use this as your strategy when reading music, feeling silences as active rather than passive things and it’ll undoubtedly add rhythmic integrity to your playing.

Feel the dots!

Here I’m talking about the type of dots which appear next to a note rather than above or below them, making them longer rather than shorter.

When reading dotted notes, consider exactly how much extra length that dot adds to the note. Many times I’ve asked children how long a dotted crotchet is, only to hear the reply, “It’s one and a bit beats”. Ah, but how big is that bit?! Knowing it’s precisely half a beat is important if you’re to place the following quaver with precision.

To place the following quaver accurately you need to feel the beats within the note. For instance this is how I would suggest counting the rhythm below. Actively counting the second and fourth beats creates a springboard for the following quavers. Do this and your dotted rhythms will be precise rather than nebulous!

Iron out the bumps

If you’ve ever played under my baton you’ll probably know this is one of my pet hates… Assuming you’re following the advice I gave in the point above, you’re now actively feeling the beats within your dotted notes. That’s a good thing, but be careful not to audibly share your technique with the listener through your breath. Often I’ll hear a distinct bump on the dot of a dotted note, or the second note of a tie, rather than a seamless continuation of the pitch. This happens because you’re thinking hard about that inner beat, maybe nodding a little with your head, or feeling the pulse through your breathing muscles. This creates a lumpy sound which isn’t attractive and it’s an easy habit to get into. To find out if you do this, play a short passage with your eyes closed, or perhaps even record it and listen back dispassionately (the voice recording app in a smartphone can be handy for this) and you’ll hear it as others do. Once you’re alert to this bad habit it’s easier to avoid and your playing with sound much smoother.

The last will be forgotten first….

Playing in extreme key signatures is a rare occurrence in recorder music as our repertoire seldom ventures beyond a couple of sharps or flats. Of course, if you have a penchant for unusual key signatures, you’re welcome to explore L'Alphabet de la musique by Johann Christian Schickhardt which contains a sonata in all 24 keys! One thing I’ve noticed over the years is the way musicians, when faced with multiple flats or sharps, will almost always forget the last element of the key signature first. This rule seems to apply regardless of the key, so in E flat major the first flat to be omitted will be the A, and in E major it’ll be the D sharps that are forgotten first. I’ve no idea why this is, but I guess there’s something about the way our brains assimilate new information which must govern this. Whatever the reason, you now know to be wary of the last sharp or flat!

Short just means short

If I had a pound for the number of times I’ve had to remind recorder players about the true meaning of staccato I’d be remarkably wealthy! So often I hear recorder players beating the living daylights out of staccato notes, with a force worthy of Norman Bates in the film Psycho. But look up staccato in any Italian dictionary and you’ll find it simply means short or detached. Perhaps you want to make the conductor realise you’ve seen the staccato markings and are implementing them, but if you don’t want to offend our ears, please don’t make them heavily accented too!

Short is a relative term

Following on from my last point, it’s worth noting that staccato doesn’t necessarily mean you should play the notes as short as possible. Instead, consider the context of your staccato notes. Quavers in an Allegro movement may indeed need to be very short, but staccato crotchets in an Andante may need to be more generous. If you like rules, perhaps aim to play notes about half the notated length as a starting point. But do listen to the result and see if it feels appropriate to the musical context. The mood and character of the music also has a bearing on the composer’s intentions and the acoustic of the room where you’re playing may come into play too. In the dry acoustic of a carpeted room staccato notes may need to be more generously proportioned, while a voluminous church acoustic might demand super-short notes because the echo will instantly lengthen the sound.

Just how long is a long note?

I often ask students how many pulses they need to feel while playing a minim, and about half of them plump for the wrong answer. Yes, a minim may be worth two beats, but where do those beats start and finish? Imagine your phrases ends with a minim, followed by a silence. That silence begins at the start of the third beat, which means the note before it should continue until the very end of the second beat. This means you must be aware of three beats when playing a two beat note if you’re not to short-change your listener. This principle applies to any long note which is followed by silence - unless, of course, your conductor tells you to do otherwise!

The arrows show how long each note sounds in relation to the beats of the bar:

Playing with style and panache

Just wiggle your fingers and blow!

If you’ve played under my baton at some point there’s a good chance you’ll have heard me utter this phrase. It may sound glib, but there’s a good reason for it. Once before I wrote about the human desire to play music perfectly, or else we’re somehow wasting our time. Now don’t get me wrong, striving for perfection is an admirable trait, but it can also tie you up in all sorts of knots. That determination to fit all the notes in can slow you down, bringing a stilted quality to the music. Sometimes you just have to throw caution to the wind, chuck your fingers onto the recorder and see what happens. It may not be pretty, but there’s a pleasure to be derived from playing with abandon and you might discover a level of fluency which surprises you. If nothing else it’ll reveal where you need to apply more focus in your next practice session.

Perfect your recorder player’s sulk

To create a warm, relaxed sound on the recorder you need to be relaxed too - any tension will soon be reflected in your tone. Before you start playing, take a deep breath and exhale with a deep sigh, allowing your face and throat muscles to go loose and floppy. Aim to retain this lack of tension as you play - allowing your face to adopt what my recorder teacher called a ‘recorder player’s sulk’. Smiling or frowning engages more muscles, creating a degree of tension in your face which can easily travel to your throat. For more tips on producing an open, relaxed tone why not take a look at the post I wrote about tone here?

Don’t forget to blow

When you consider all the things we have to think about while playing the recorder, there’s a lot of multitasking involved - reading notation, breathing, tone, fingering, articulation and more besides. As we become more proficient we learn to juggle these competing tasks, but every musician has limits. When I’m working with adult recorder groups I see this firsthand in two situations - when the music suddenly becomes much busier, or when the players are faced with lots of unusual accidentals. At these points both the quality and quantity of tone often suffer because the players’ brains are instantly distracted by the need to tongue more quickly or to interpret the notation swiftly. I’m afraid I don’t have a magical solution for this one, but self awareness is a powerful tool.

Next time you’re faced with an unexpected flurry of semiquavers ask yourself if your tone quality has suffered because you’ve forgotten about the need to support your breath momentarily. If your recorder is beginning to sound like a wheezy donkey you know what you need to do!

Play with positivity

If you lack confidence it’s tempting to play more quietly, believing you can hide among the massed ranks of players in your local recorder ensemble. In many walks of being a shrinking violet helps you blend into the crowd, but sadly this isn’t the case with recorder playing.

When instruments are manufactured they’re designed to be played at a specific pitch, so each note rings out at the right frequency. In contrast, when you under-blow some notes will sound flatter than others and many of the highest pitches simply won’t sing reliably. Added to that, your tone will be weedy and undernourished. The result? Your playing will stand out from the crowd much more than you intended, and probably not in a good way! It might sound counterintuitive, but use a firm, well supported breath pressure and you’ll find it much easier it blend in.

I often use the word gumption in relation to playing with positivity. What do you think of if someone is described as having gumption? In my mind it’s a person who has a positive, can-do attitude, who will go for it and make things happen. You won’t find them cowering timidly in the back row. Have this in mind as you play your recorder and I bet you’ll make a more confident sound straight away.

Make your mistakes with style and panache!

Following on from my encouragement to play with gumption, you might be thinking, “But what if I make a mistake? Everyone will hear it!” Yes, that might be true, but we learn from our mistakes, so being able to hear you’ve gone wrong is no bad thing. Tentative recorder playing often leads to a mushy rhythm as you gingerly dip your toe into new musical waters. In my book mushy rhythms are never a good thing! It’s much better to play with positivity (gumption) because your tone and rhythm are both likely to be improved. You’ll also hear your errors more clearly and be in a good position to correct them. Now I’m not advocating making loud and proud mistakes in a concert situation - by that stage you should have practised the music enough to iron them out. But when rehearsing, own your mistakes and make them with style and panache!

Give yourself an improvement target

A strategy I’ve tried recently is to set ensembles a target when we’re rehearsing. For instance, I might ask the tenors to project their sound 56% more so a melody cuts through the texture, or perhaps I’ll instruct the contrabasses to play their staccato notes 48% shorter. The precise figure rarely matters (although a very specific number often elicits a chuckle from the musicians) but the simple act of providing a target usually puts us on the right musical path. Try this in relation to a specific task when you’re practising and you might find it does the trick.

Tuning trumps dynamics

The recorder may have a limited dynamic range compared to many other instruments, but it’s still entirely possible to play expressively. For really convincing dynamic contrasts alternative fingerings play an important role and I plan to write more about this in a future post. If you’re not yet comfortable using different fingerings for loud and soft effects it’s tempting to use breath pressure to create these contrasts. Yes, slowing the flow of your breath will make the notes quieter, but go too far and your intonation will also become flatter.

When faced with an extreme dynamic changes in a piece of music by all means experiment, but ultimately I would argue that intonation is more important than dynamics. It’s all very well playing an exquisitely soft passage, but if you leave your listener squirming uncomfortably in their seat because the music is painfully out of tune that positive effect is greatly diminished! In the long term make a point of getting to know some creative alternative fingerings so you can achieve dynamics and good intonation, but remember this will probably need to be a gradual process.

The holy grail of recorder playing - a true legato

One thing which will make you stand out from the crown as a recorder player is being able to sustain a genuinely legato melodic line, with a well supported tone throughout. If you can cultivate a rounded sound while playing with articulation which is super-smooth you’ll bring a new level of expression to your melodic lines.

The words I come back to time after time are singing and fluidity. Aim to sustain your breath and create a sense of connectivity between the notes, just as you would when singing a hymn tune, and you’ll be well on your way. Think of the breath you put into your recorder like a stream following a crease in the hillside and that’ll help you sustain right through a phrase.

I’ve written a whole blog about this topic, which you can find here.

Breathing is good!

Once again we come back to the thorny issue of multitasking. Breath is the lifeblood of our sound, yet when we get distracted by tricky rhythms and challenging fingering it’s so easy to forget this fundamental activity. Breathing is a vital thing to do, whether in every day life or playing the recorder, so don’t be afraid to stop, take a good lungful of air, and regroup - you body and recorder playing will thank you!

If you find it hard to make space to breathe while playing why not take a look at my blog in this topic?

Get a head start with Baroque style

Most modern music is littered with instructions from the composer, showing you his or her creative intentions. In contrast, Baroque music can seem a bewilderingly blank canvas, with little in the way of expressive instruction. Tempting as it may be to just play the notes and rhythms, you’ll achieve a decent basic baroque style by using these simple guidelines.

In faster music (say Allegro or Vivace) look the notation and identify the smallest note values you have (perhaps semiquavers or quavers, depending on the time signature). These should generally be played quite smoothly. Now look for the second shortest note values - these can be more detached.

Bear in mind that this isn’t a rule, but merely a guideline which can be broken. If the second shortest notes are repeating pitches, or leaping around, playing them detached will almost certainly create the basics of a good Baroque style. But if you have stepwise (scale) passage you might choose to break this ‘rule’ and play them more smoothly. Be open to trying different things and take every opportunity to listen to recordings of professionals playing Baroque music so you can learn from their example.

Be brave - sit in the front row!

Time and again I go to conduct an ensemble and I’m faced with a row of empty seats directly in front of me. Why does no one want to sit in the front row? Do they think I’m scary, or perhaps I’ll ask them to play a solo? Whatever the answer, I’m on a mission to persuade people that the best seat in the house is in the front row.

Ask any school teacher and they’ll tell you they always look to the back row for the troublemakers, but that’s not the reason why I recommend the front row. The recorder is a very directional instrument, so if you’re at the back of a large group (a massed playing session at a festival, for instance) you’ll hear very little of those sitting in the front row. However, those brave souls sitting right by the conductor get to luxuriate in a wash of sound from those sitting behind them. This creates a real sense of togetherness and gives them the confidence to play to the best of their abilities. Even better, if your ears aren’t as good as in your youth you’ll find it much easier to hear the conductor’s helpful advice. Go on, making it your new year’s resolution for 2024 to sit in the front row and find out for yourself that it’s the best seat in the house!

Eliminate the chiff

When we first learn the recorder we tend to start with a small instrument - perhaps a descant or treble. As we progress we expand our horizons, often trying larger recorders - perhaps the bass or even bigger. It’s easy to assume the techniques we used on the descant will work just as well on the low instruments but some of them need a little modification. I’m thinking specifically about tonguing. Using strong articulation on a descant recorder will often do little harm, but the same level of attack on a bass can create a very explosive sound - often known as chiffing. Think of the sibilant sound you hear when a steam train sets off. A nostalgic sound at a heritage railway, but in the context of a recorder orchestra it can wreck the mood and destroy any semblance of a legato musical line!

Yes, there are places where this percussive effect may be desirable, but you do at least need to be able to turn it off at will. My advice is to make the gentleness of your tonguing inversely proportional to the size of recorder. On a contrabass you tongue should make the softest of contacts with the hard palate in your mouth, keeping further back from your top teeth, so it imperceptibly interrupts the airflow. Most importantly of all, listen critically to your playing and ask if your articulation sounds appropriate to the musical style. If the answer is no, you need to do something about that!

Make your intentions clear

My final thought is one that occurred to me while teaching online during the pandemic. Clarity is often lost via this medium, but I’ve since found the following a useful concept in person too.

Many of us were brought up to be well mannered we’ll have an innate worry about being tasteless and over the top, Being polite is one thing, but sometimes you have to exaggerate ideas to get your point across. Think of actors on stage. Instead of speaking as we would in conversation, they amplify their gestures and tone to project to the whole theatre. Don’t be afraid to do the same with your recorder playing. Whether you’re using varied articulation, contrasting dynamics or changes of tempo, you need to make your intent clear. In a concert situation, only a proportion of your gestures will reach your audience who may be sitting a long distance away.

My advice is to imagine your listener is sitting with a copy of the score in front of them, pencil in hand. If your performance has sufficient clarity of intent they should be able to listen to you and annotate the music to reflect what they’re hearing. You could even test yourself by recording your playing and listen back with a clean copy of the score in hand. Could you honestly notate the details you hear? If the answer is no, you know what you need to do!

~ ~ ~

No doubt I’ll come up with more ideas in the coming months, but that little collection should give you plenty of food for thought. Are there other topics you consider regularly when playing, or gems of knowledge you’ve picked up from other teachers? Why not share some of them in the comments below - it’ll be fascinating to learn from each other’s experiences.