What’s your favourite era of music? Is there a style of music that communicates to you more clearly than others? Teachers often refer to different periods of music, but what do we actually mean by Renaissance or Romantic music?

Like art and architecture, music is generally defined as belonging to particular stylistic eras. There are often features in common between these genres - for instance ornate decoration is a characteristic of both Baroque architecture and music. But there are also other terms too, which describe particular styles of music, as much as the period of history in which they were composed. At the most basic level, musical eras are divided up into periods of time, as follows:

Medieval up to around 1400

Renaissance 1400-1600

Baroque 1600-1750

Classical 1750-1820

Romantic 1820-1900

Modern/Contemporary 1900 onwards

While these dates are a useful guide, music doesn’t necessarily fit neatly into them, as we’ll see. Some composers were rule breakers, ahead of their time - think of Carlo Gesualdo, composing extraordinary harmonies in the Renaissance, some of which still feel extreme today. In contrast, we have composers like Elgar whose music is firmly rooted in the Romantic style, even though he was writing at the same time as modernists like Schoenberg. As a result the boundaries become rather blurred, so the dates above are a rough guideline rather than strict rules.

Having a sound knowledge of these different periods of music will undoubtedly help you understand the repertoire you play more easily - a composer’s intentions often become clearer when we understand the context in which they were writing. Of course there are some periods in which our instrument, the recorder, barely featured at all. That’s not to say we won’t play music from the Classical and Romantic periods, but in order to do so, we have to be prepared to borrow repertoire from other instruments.

In this blog post, I’m going to focus on three periods of music, returning to later eras in a future post. My original intention was to cover the whole of western classical music, but I quickly realised doing so would result in something worthy of an entire book, rather than a single blog post! Let’s make a start with the earliest years of formal music making…

Medieval Music

Humans have been making music in one way or another since our species first evolved. Initially we used our voices, but instruments made from animal bones have been found from 60,000 years ago. By the start of the Medieval period, music had become intrinsically linked with the church and it was here that vocal music first flourished. This earliest music can be described as monophony - that is a single line of plainsong, sung in unison. Over time this expanded into organum, where two lines were sung in parallel, a fourth or fifth apart - the simplest form of harmony.

But music wasn’t purely used in religious settings. Troubadors travelled throughout Europe, singing secular songs, often about courtly love. These musicians would have accompanied their singing with instruments such as the lute, dulcimer, vielle, psaltery and hurdy-gurdy. Wind instruments, such as the recorder and flute, were also common, as well as simple brass instruments and percussion.

An Ars Subtilior manuscript

Gradually polyphonic music developed during the Medieval period - the use of multiple lines working independently of each other - by composers such as Machaut and Perotin. Later still, in southern France, music of even greater complexity evolved - Ars Subtilior. This was mostly secular vocal music, with enormous rhythmic complexity - some of it unmatched until the 20th century.

A selection of Medieval composers

Hildegard of Bingen, Léonin, Pérotin, Guillaume de Machaut, Francesco Landini, John Dunstable.

A musical Renaissance

By the time we reach the Renaissance, music was an important feature of all parts of life, appearing in religious, civic and courtly settings.

Early in the Renaissance, the church was still the most significant setting for music and many composers wrote motets and masses for this purpose, usually based around Latin texts. Polyphonic music had now become the norm, with parts moving independently of each other, and lots of imitation between the voices.

A Renaissance printed part book

The advent of printing allowed music to be published at an ever greater rate, with much of it aimed at amateur musicians. Secular vocal music, such as chansons and madrigals, and instrumental music too, was published in partbooks which could be used in a domestic setting. Before this music had to be copied by hand, a very time-consuming and expensive process, and the advent of printing allowed music to be disseminated much more widely and speedily.

Many different forms of instrumental music developed during this period, including forms such as the toccata, prelude, ricercar and canzona, as well as many types of music for dancing. The Canzona gradually evolved into the sonata, a form which composes continue to us to this day. I’ve written a blog all about the evolution from the canzona to the sonata which you can read here.

Madrigals became one of the most popular types of secular vocal music during the Renaissance, and composers typically used word painting to depict the text they were setting. For instance, in Thomas Weelkes’ As Vesta was from Latmos Hill Descending when the text talks of running down the hill we hear the notes in scurrying downward runs.

Renaissance instruments

A bass viol or viola da gamba

The Renaissance saw many developments in musical instruments. The viol family became very became very popular and a huge repertoire of music developed for this family of instruments. Viols (not to be confused with the violin family, which we’ll look at later) have sloping shoulders and a flat back, with six strings (occasionally seven for the bass viol) and frets on the fingerboard to help the player with intonation. Like the recorder, they come in several sizes, from treble down to bass and consort music was composed for endless combinations of treble, tenor and bass viols. This consort repertoire included standalone pieces, such as Fantasias, but dance music too became very popular. Many composers wrote sets of dances, often pairing the Pavan with a faster dance such as the Galliard. I’ve written in more detail about Renaissance dance music here if you’d like to learn more about this topic.

Wind instruments were also popular in the Renaissance, such as the recorder and flute, and they were sometimes combined with strings in broken consorts. Music formed a large part of life in the royal court, in religious, domestic and ceremonial settings. Henry VIII in particular employed a large number of musicians, including a court recorder consort based around the Bassano family.

Precursors to many of today’s instruments developed during the Renaissance, including the violin, lute, guitar, curtal (predecessor to the bassoon) and sackbut (an early form of trombone). These presented composers with an ever greater array of musical colours to explore, although the precise instrumentation was rarely specified in the music. Of course this gives us carte blanche as recorder players to explore any type of music from this period!

The following video features a consort of sackbuts and cornetts. The cornett uses a cupped mouthpiece, much like the trumpet, while the body is made of leather-covered wood and fingered much like a recorder.

Harmony and ornamentation

Although complex polyphonic writing was common during the Renaissance, composers still used simple major and minor harmonies, saving dissonances for special effects and moments of high tension. One harmonic curiosity existed in English music of this period - the use of false relations. This is a simultaneous clash of major and minor harmonies, often at the end of phrases, as rising and falling melodic minor scales meet with each other, as you can hear in the video below. These piquant harmonies are particularly prevalent in the music of composers such as Thomas Tallis and William Byrd.

Another innovation during the Renaissance was the development of ornamentation, in the form of divisions. In contrast to the free trills and embellishments we encounter in Baroque music, Renaissance ornamentation is more structured, with melodic lines being mathematically divided into smaller note values. Sylvestro Ganassi wrote a very detailed treatise teaching the art of divisions, Opera intitulata Fontegara (pictured below), and performers of the day would have been well versed in adding such decorations to the music spontaneously.

The cover of Ganassi’s Opera intitulata Fontegara

A selection of Renaissance composers

Guillaume Dufay, Johannes Ockeghem, Jacob Obrecht, John Taverner, Claudin de Sermisy, Tielman Susato, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Orlando de Lassus, Andrea & Giovanni Gabrieli, William Byrd, Maddalena Casulana, Anthony Holborne, Elway Bevin, Thomas Morley, Peter Philips, William Brade, Claudio Monteverdi, Thomas Lupo, John Wilbye, Giovanni Coperario, Thomas Weelkes, Michael East, Samuel Scheidt, John Dowland.

The Baroque - a musical pearl

Next we come to a period beloved by recorder players - the Baroque. The word itself comes from the Portuguese barocco - an oddly shaped pearl - which hints at the ornamental character of music from this period, stretching from Monteverdi to Bach.

While Baroque music had distinct national styles, these became ever more fluid as people travelled more widely. 17th century London, for instance, was a tremendously popular location for musicians, and became a melting pot of composers from all over Europe. The type of music a composer wrote was often dictated by their employer and location. For instance, J.S.Bach wrote lots of sacred music because he was employed by the church, while Henry Purcell wrote many works for the London theatre scene.

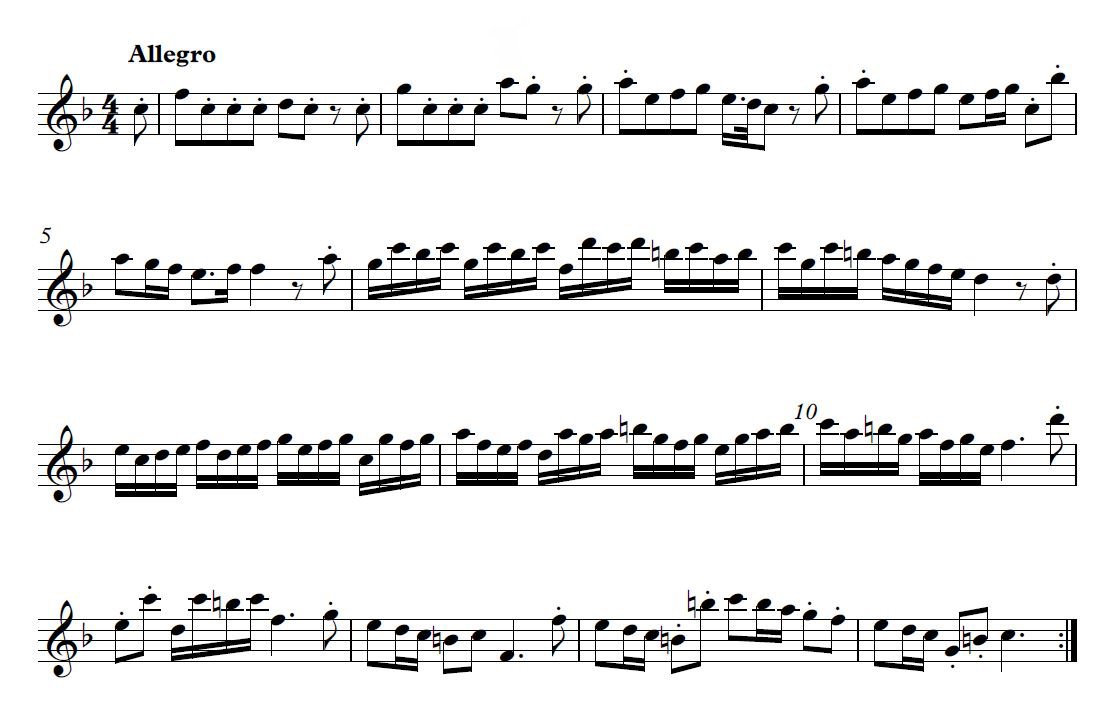

A movement from Telemann’s Methodical Sonatas, showing a simple melodic line and how it could be ornamented. Click on the image to see it enlarged.

Ornamentation developed from the divisions of the Renaissance, into much freer but equally florid decorations, including the trills we perhaps most closely associate with Baroque music. Again, several composers (Quantz perhaps being the most famous) wrote treatises on the art of ornamentation, while others composed music with sample ornamentation as didactic resources - for instance, Telemann’s Methodical Sonatas.

In contrast to the Renaissance, polyphony became less important and the concept of a melody with an accompaniment became more prevalent. This was the period where basso continuo developed - a style of accompaniment usually played by a sustaining bass instrument, such as the cello, with a keyboard instrument (harpsichord or organ) providing the harmonies. Rather than prescribing precise notes for the keyboard player, composers simply indicated the harmonies they desired with numbers – figured bass – written above or beneath the bassline. This is a type of shorthand, which may seem impenetrable at first glance, but allows immense freedom for the harpsichordist. With practice a skilled continuo player can interpret the numbers very quickly and add lots of character to the music.

An extract from a recorder sonata by Francesco Mancini, with figured bass above the bassline

The idea of writing for specific instruments became much more common, allowing composers the ability to create carefully planned contrasts of musical colour. That said, it was also common for publishers to suggest a sonata could be played on a variety of instruments (flute, oboe or recorder, for instance) - no doubt a ploy to sell more copies of the music! Baroque composers began to write solo and trio sonatas for specific instruments and continuo, and it was during this period that the concept of a Concerto for soloist and orchestra evolved. The solo parts in concerti were often highly virtuosic – a feature that was retained and expanded during the Classical and Romantic periods.

Another huge development during the Baroque was opera. The genre evolved a long way during the period, from the free flowing writing of Monteverdi to Handel’s very formal Italian operas of the late Baroque. Opera featured two distinct types of music - recitative and arias. Recitative was a musical imitation of speech, usually for a singer with basso continuo accompaniment, and its purpose was to move the storyline forward. In contrast, the aria was a moment for an operatic character to express how they were feeling about what had just happened. These usually had an orchestral accompaniment and gave singers a chance to demonstrate their enormous virtuosity. At this time it was common for men to take all of the leading roles, even playing female characters. The highest, dramatic roles were most often given to men with castrato voices, with best castrati, such as Farinelli and Senesino, commanding huge fees and mass adulation – the equivalent of a modern day Hollywood star. Lower voices tended to be used for comic roles.

Dance music also continued to thrive during the Baroque, although the dances themselves evolved. Out went the Pavan and Galliard, and in came the Gavotte and Minuet. If dance music of this period particularly interests you I’ve written a blog all about the dances which you can find here.

Baroque performance practice

In common with music of the Renaissance, most Baroque composers gave very little information in their music regarding the way it should be played. Performers of the day would have been taught what was expected of them in terms of articulation, phrasing, dynamics and more. But for those wishing to learn more, numerous treatises were published during this era to help performers. For recorder players, the notable sources of advice are by Ganassi and Dalla Casa in the Renaissance, with Hotteterre and Quantz during the Baroque. But if you’re interested in looking for advice from either period, I can recommend this article which shares a comprehensive list of historical treatises.

Instrumental evolution

There were continued developments in musical instruments during the Baroque period, with composers taking advantage of these innovations. The Baroque orchestra was based around an ensemble of strings, as are today’s orchestras, usually with harpsichord continuo adding colour and texture, as well as filling out the harmonies. The instruments used were almost all members of the violin family - violins, violas and cellos. Sometimes you’d have an instrument doubling the cello line an octave lower - either a double bass (with four strings, like the cello) or violone (which had up to six strings). The popularity of the viol family gradually waned during the Baroque, and Purcell’s astonishing Fantasias (composed at the tender age of 21) are some of the last consort works for viols. The bass viol or viola da gamba persisted though, often used in chamber music as both a continuo or solo instrument.

Baroque violin

The violin family became the most important string instruments of the Baroque. Compared to the viol, they have rounded shoulders, a curved back and f-shaped tone holes in the front of the instrument. Both the viol and violin were strung with gut strings (today’s violins use metal strings), so they produce a softer, less strident tone than their modern counterparts. The Italian city of Cremona became a hugely important hub for luthiers (makers of violins, violas and cellos) during the Baroque, with the most talented makers creating instruments which are still in use today. Violins by Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri are played today by the world’s top virtuosos, although many have been modified and strengthened to suit the greater technical demands of 19th century repertoire.

A Baroque oboe, with fewer keys than its modern counterpart

Woodwind instruments were often added to orchestras to create extra colour - perhaps a bassoon doubling the bassline and oboe, recorder and flute player higher lines. It was common for Baroque woodwind players to be multi-instrumentalists, playing oboe, flute and recorder in the same work, switching between movements. It was only in the Classical period that it became the norm to specialise on a single woodwind instrument.

Some composers also add brass instruments into the mix from time to time - notably the trumpet and horn. At this point they were made from simple lengths of bent and coiled metal, with no valves or pistons, so players had to use their embouchure (shaping the lips and surrounding muscles) to play different pitches in the instrument’s native harmonic series. This also meant each instrument could only play in one key. If a composer chose to use the horn or trumpet in a movement with a different key signature, the player would need to remove a section of tubing, replacing it with one of a different length to make the instrument longer or shorter, thus changing its native key.

A Baroque trumpet

Composers of the Baroque

Johann Heinrich Schmelzer, Johann Christoph Pezel, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Matthew Locke, Henry Purcell, Arcangelo Corelli, Jean-Baptiste Loeillet, Johann Mattheson, Georg Philipp Telemann, James Paisible, Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Friedric Handel, Domenico & Alessandro Scarlatti, Johann Joachim Quantz.

If you want to explore the music from these periods for yourself, clicking on the composer links will take you to some of my favourites from the consort music I’ve shared with you over the last five years.

So there I’ll pause our exploration of the many musical periods - the remaining eras will follow in a future blog. We stop at the recorder’s high point, with the prospect of more than 150 years to be spent in the shadows. However, a second heyday is still to come, about which more very soon!