Do you make your recorder sing? No, I don’t mean singing into your recorder, but instead I’m talking about playing a genuinely legato, singing line. This is one aspect of technique many people find difficult. But if you can master this, your playing will really stand out from the crowd.

Photo by Steven Erixon

If you think about it, the process of playing the recorder isn’t so different from the way we sing. The breathing technique you use is fundamentally the same, as are the muscles used to control the way breath leaves your lungs and enters the recorder. The big difference is of course the way the sound is produced. When singing, your vocal chords creating vibrations in the air column, while on the recorder this role is taken by the instrument’s labium. Similarly, in both recorder playing and singing we use our tongue and mouth to articulate words or notes clearly.

This parallel wasn’t lost of musicians of the Renaissance and Baroque. In his 1535 treatise, Opera Intitulata Fontegara, Sylvestro Ganassi says the following about playing the recorder:

“…just as a gifted painter can reproduce all the creations of nature by varying his colours, you can imitate the expression of the human voice on a wind or a stringed instrument. The painter reproduces the works of nature in varied colours because these colours exist in nature. Even so with the human voice which also varies the sound with more or less boldness according to what it wishes to express. And just as a painter imitates natural effects by using various colours, an instrument can imitate the expression of the human voice by varying the pressure of the breath and shading the tone by means of suitable fingering. In this matter I have had much experience and I have heard that it is possible with some players to perceive, as it were, words to their music; thus one may truly say that with this instrument only the form of the human body is absent, just as in a fine picture, only the breath is lacking. This should convince you that the aim of the recorder player is to imitate as closely as possible all the capabilities of the human voice.”

As Ganassi suggests, it takes much subtlety of articulation and fingering to perfectly imitate the infinite variety of the human voice, but for today we’re going to focus on creating a genuinely singing legato.

What do we mean by legato?

Type the word legato into an Italian-English dictionary and it’ll be translated as bound, connected or tied. For musical purposes, connected is perhaps the best of these, as the term is used to indicate a passage which should be played smoothly - that is connecting the notes to each other as closely as possible.

Is this the same as slurring?

This is a misconception I often encounter. When a musical phrase is printed with a long, curved line above or beneath it, the composer is asking you to articulate (tongue) the first note and then continue the rest of the phrase without tonguing, creating a silky smooth effect. Yes, the result is legato, but a genuinely smooth phrase doesn’t have to be slurred. It’s this non-slurred form of legato I’m talking about today as it’s the type you’ll need most often when playing the recorder. For this type of legato you’ll be tonguing every note, while still connecting them as closely as possible.

Do you sing?

Now, I know many recorder players also sing - for instance in a choir, maybe in church, or perhaps just while you’re in the bath. Maybe you class yourself purely as an instrumentalist, but I’m still going to ask you to sing. Don’t be afraid - I’m not expecting perfect operatic tones - this is just a means to an end. If you’re not a natural singer maybe find a quiet room where you can hum a tune without being self conscious - no one else need listen.

Sing a familiar tune to yourself, or maybe just sing a few notes of a scale. What do you notice about the way the notes are connected? Do you sing each note as individual, separate sounds, or do you naturally join them up? I’m willing to bet it’ll be the latter… When we sing it’s very natural to connect the notes together, because singing is one of those things we do from a young age, whether it’s nursery rhymes or humming along to your favourite song on the radio. For instance, listen to this beautiful rendition of Scarborough Fair by Rachel Hardy and notice how smoothly she shapes the lyrical melody.

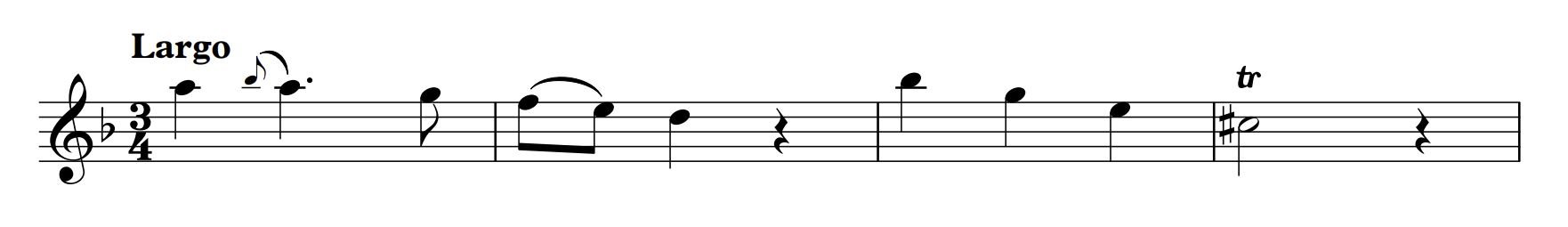

Now think about your recorder playing. Do your musical lines have the same feeling of connection between the notes? If you were to record yourself playing, would you hear the same degree of smoothness when you listened back to it afterwards? If you’re not sure of the answer, why not do exactly that? If you have a smart phone it’ll almost certainly have a voice memo app you can use - no fancy equipment is needed. Pick a simple tune so you’re not overstretching your technique - if you’re stuck for ideas, click here for Jacob Van Eyck’s melody Daphne.

Now listen back to your recording. What did you notice? Were your notes beautifully connected, or did you notice some lumps, bumps and gaps? It’s easier to be dispassionate and critical when hearing your playing once removed, isn’t it? Now you’ve made a recording I suggest you save it - it’'ll be useful for comparison later.

Let me show you what I mean by a genuine, singing legato on the recorder, with a movement by Bach from my CD, Helen and Friends. Notice how I connect the notes to each other to create a sense of line.

How do I create a singing legato?

There are three crucial elements if you’re going to playing a genuinely legato melodic line - breath, tongue and fingers. Let’s take a look at the effect each one has on the end result.

Optimising your breath

When you listen to the Bach Adagio above, what makes the sound smooth and creamy? It’s the constant stream of air, isn’t it?

The most important thing needed for a perfect legato is continuity of breath. If the breath is constantly interrupted the result is a choppy, inconsistent sound. There are many reasons why this might happen and we’ll explore some of those in a moment.

For now though, the important thing is to keep blowing, right the way through each phrase - no matter whether you’re tonguing or slurring the notes. Let’s try this out straight away with a simple hymn tune, St Clement. I suggest you begin with a smallish recorder - these versions will work on descant, treble or tenor.

Begin by playing the melody entirely slurred - just tongue the first note of each phrase and then let your breath and fingers carry you through until the next breath mark. But look out for the one repeated note where you will need to tongue once more.

Here’s my version:

Don’t worry if your version doesn’t sound quite this smooth and creamy yet - we’ll fix that in a moment. The important thing is to keep the air flowing at all times, even if things get a little bumpy at first. Slurring forces you to keep the air flowing all the time - this should also be your aim when you start tonguing again.

Another crucial consideration when playing a singing line is the speed of breath for any given note. If you haven’t already read my post about developing your tone, now would be a good time to do so as I covered all the basics to get you started. Of course, if you have read it there’s no reason why you shouldn’t return for a refresher! You can find my post on tone here - it’ll open in a new tab or window on your browser so you won’t lose your place here.

It’s important to remember your recorder requires a different speed of breath depending on where you’re playing on the instrument - bottom notes need slower, gentle breath, while high notes require faster breath to create the optimum sound. This is something you need to consider while playing any melodic line but it’ll be especially noticeable in a simple tune like St Clement. Listen to my recording above again and notice how I subtly increase the speed of breath for the higher notes than the low ones, to ensure I’m always making the best possible tone. Tailoring the speed of your breath for the range you’re playing in is an important part in creating a smooth, singing line.

To practise this breath control further it’s important to use easy melodies at first - try and do this with something fast and whizzy and you’ll be distracted by your fingers. Hymn tunes or slow folk melodies are perfect for this, but you could just as easily use simple, slow scales and arpeggios for the same purpose. If you’re a Score Lines subscriber you’ll find some handy scale sheets to download over in your Members’ Area.

Don’t let your tongue interrupt the flow

As you get used to this continuity of air flow while slurring, the next step is to introduce some articulation.

We often talk about using particular letters to articulate notes - such as D or T. I would take this a step further and add an ‘ooo’ sound after your chosen letter - ‘doooo’ or ‘toooo’. This gives a greater sense of the air flow and will help you get that longer, smoother feel.

Which letter should I use?

Say the word ‘doo’ to yourself and note the way your tongue moves within your mouth. The tip of your tongue lifts and makes contact, briefly, with the hard palate - that crinkly feeling ridge just behind your top front teeth. It’s this contact which creates the clean start to each note. If you now say ‘too’, notice how it has a slightly stronger effect. Both are valid for recorder playing, but for a genuine legato you need to minimise the strength of the articulation as much as possible, so I would use ‘doo’ for best results.

Minimise interruptions to the flow of air

Now experiment with this articulation (without a recorder for now), saying ‘doo’ in different ways - with a firm D and then with a softer, less explosive one. It’s this latter, gentler ‘doo’ you need to hone if you’re to play a really smooth, singing line. Try shaping your tongue in different ways and notice how the the articulation is softer and smoother when your tongue remains in contact with the hard palate for as little time as possible. It’s important to remember that all the time your tongue remains in contact behind your teeth it’s stopping the air flowing into your recorder, creating gaps in the sound.

It’s also worth experimenting with a ‘looo’ articulation. If you compare ‘doo’ and ‘loo’ you’ll notice you’re fundamentally making the same tongue movement, but the contact with your hard palate is even gentler for ‘loo’. If you find your ‘doo’ tonguing is still a little too explosive, try using ‘loo’ instead.

Now try the same tongue strokes while playing slow, repeated notes on a recorder. Focus on keeping the breath flowing at all times and ensure your tongue interrupts this stream of air as little as possible. Don’t forget to think about the quality of your tone too - it’s easy to forget this while you’re concentrating on your tongue!

If you can produce a line of beautifully connected. steady repeated notes (speed is not required yet) you’re well on the way to being able to play a singing legato line. To give you an aural example, here’s a simple recording of me playing repeated notes, each time the pitch changes I alter my tonguing, first from ‘too’ to ‘doo’ and then to ‘loo’. Notice how the gaps between the notes become smaller and the connection between them increases.

Keeping your fingers neat

One of the habits I frequently notice among recorder players is a propensity for their legato playing to suffer as soon as the notes get harder. As soon as we hit a fast passage, or one that’s peppered with accidentals, we naturally concentrate more on what our fingers are doing. It’s a simple matter of multitasking - there are only so many things we can think about simultaneously. What’s the result? A choppy sound, which has little sense of line or continuity. Listen to this example, an extract from one of Handel’s recorder sonatas, first played as I often initially hear it in recorder lessons, and secondly with more attention focused on maintaining a smooth articulation.

Extract from Handel Sonata in B flat

Now, of course, I was hamming that up a little for the microphone, but it’s still a fairly true representation of what I often hear! The scales are quite straightforward to play, but once the music begins to leap through arpeggios in line two, more finger movements are required (including a tricky cross fingering for E flat) and the brain naturally focuses on those more than their smoothness. That particular extract was from an Allegro, but the same problem can occur in slow moving music.

Don’t neglect the quality of your finger movements

Now go back to smoothly play the hymn tune St Clement again, but this time think about the way you’re moving your fingers.

With a slow piece like this, would you expect your fingers to move quickly or slowly between notes? If your instinctive answer is ‘slowly’ I’m afraid you’re wrong - your fingers must always move quickly, regardless of the tempo. I often pose this question to players I coach and there are always a number who fall into the trap I’ve laid!

Think for a moment about how much space there is between the notes when you’re playing really smoothly… There’s almost no space at all, is there? This means if you move your fingers slowly you’ll hear all sorts of blips and slurps between the notes as the change between fingerings takes too long. If instead you focus on making really quick, neat finger movements you’ll find your fingering is more rhythmic and it’ll fit neatly with your legato tonguing. For instance, listen to this second recording of St Clement, this time played with every note tongued as smoothly as possible. You’ll hear the transitions between notes are clean and the overall effect is almost as silky smooth as the slurred version you heard earlier.

The challenges of playing an eighteenth century instrument

The design of the recorder has more or less been frozen in time since the 18th century. Unlike the flute or oboe, our instrument hasn’t gained extra keys to simplify the fingering (aside from those added to ease long stretches on larger recorders). Because of this, we have to deal with more complex finger patterns for some notes - think of the awkward cross fingering we use for E flat (treble recorder) or B flat (descant/tenor). These forked or cross fingerings mean your thirds fingers (which are naturally weaker than the others) often have to work independently of the others. This is why music with lots of sharps or flats is harder to play on the recorder.

So often I hear awkward passages (be they fast or in difficult keys) being played less smoothly than sections where the fingerings are easy. I guess it’s an instinctive piece of compensation by our brains. Somewhere in our subconscious we know that if we create more space between each note (effectively playing staccato) that gives our fingers more time to get to that difficult fingering!

I don’t have a magic bullet for this problem, but if you find yourself falling into this trap don’t be afraid to slow the music down and tidy up your fingering. Once you’re able to negotiate difficult fingerings neatly and with ease, that then frees up more of your brain to think about tonguing smoothly too. While playing smoothly in slow music is simpler (you have more thinking time), if you’re aware of this potential pitfall you’re in a much stronger position to avoid it.

Developing your sense of line

So what can you do to improve your legato tonguing and create the mellifluous singing line we’re after? Here are my top tips…

Practise regularly - The best way to turn good technique into something you do habitually is to do it as often as possible! If you’re short of practice time, at least make sure you spend a few minutes every day playing really smoothly. Little and often will be much more effective than a big splurge of practice once a week.

Start with something simple - Don’t try and work on your legato lines with a Vivaldi concerto - you’ll get distracted by all the whizzy notes! Instead, pick a simple, slow melody or an easy scale and use that to really focus on the quality of your legato.

Build up gradually - Once you can habitually play your simple melody with a beautiful singing line you can then move on to something more challenging. Do it gradually, perhaps picking something a little quicker, or a piece with more complex finger patterns. Don’t push yourself too far too soon and don’t be afraid to take a step back to something simpler for a refresh from time to time.

Record your playing - Use the voice memo app on your phone, or another recording device, to record yourself from time to time. Maybe pick a simple melody and record yourself playing it once a week. After a few weeks go back and compare the recordings - if you’ve been listening critically to yourself and working diligently you’ll hear a difference.

Listen to other recorder players - Go onto the internet or your favourite music streaming service and search for professional performers playing. Really listen to their performances and analyse what they’re doing. As Oscar Wilde once said, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” You don’t need to imitate every last detail you hear in another recorder player’s performance, but you’ll learn a lot by listening critically to those who’ve spent a lifetime honing their skills to share with the rest of us. To get you started, here are a few recordings where the performers achieve a deliciously legato singing line, bringing their recorder as close to the human voice as Ganassi said we should.

~ ~ ~

Marion Verbruggen playing Amarilli mia bella by Jacob van Eyck

Piers Adams performing Dido’s Lament by Henry Purcell from Bach Side of the Moon.

The Flautadors playing Pavan No.13 by Anthony Holborne

Dan Laurin performing the second movement of York Bowen’s Sonatina for recorder and piano

Erik Bosgraaf performing the Sarabande from Bach’s Partita BWV1013

If you have tips of your own please do leave a comment below and share them with us. Maybe your teacher gave you a great way to play smoothly, or perhaps there’s a gorgeous recording you’ve discovered which you love to try and emulate when playing smoothly. Let’s share our ideas and work on this together!