The human brain is a marvellous creation - capable of amazing feats of mental gymnastics. Yet there are moments when somehow our brains spontaneously go off piste, taking us on a completely unintended path. Why is this, and what can we do about it?

In particular I’m thinking today about the challenges of playing different sizes of recorder. As recorder players we’re required to become the musical butterflies, flitting from one size of instrument to the next, with a mix of different fingerings and clefs. I’m willing to bet, like me, you’ve had moments where it all goes wrong and you randomly switch into the wrong fingering, for no apparent reason. Am I right? This is a problem recorder players often fret about, but in my experience, it’s completely normal.

I’ve been teaching for over 30 years and in that time I’ve only encountered one pupil who never experienced this. That child, around the age of 9, began exploring treble fingering after playing the descant for a year or two and, as far as I can recall, never suffered any confusion between the two sets of fingerings. Rest assured, she’s a complete outlier - an exception to the norm. You’d think, as a professional recorder player, I’d be immune to such confusion, wouldn’t you? Oh no, I’ve even been known to occasionally slip into both the wrong fingering and the wrong clef at the same time - double the catastrophe!

Why does this happen? The fundamental problem is the fact that the recorder family commonly uses two distinct sets of fingerings - C and F. This means when you’re playing the descant or tenor, the bottom note (all fingerholes covered) is C, while on the treble and bass the same fingering will elicit an F. We take this for granted, but there could, arguably, have been a better way.

Take the brass family for instance. Every brass instrument with piston valves (trumpet, cornet, euphonium, tuba etc) uses one set of fingerings. If you have lips with sufficient flexibility you could switch from trumpet to tuba in a matter of moments, using precisely the same fingerings. In a brass band everyone even plays in the same clef - including the huge B flat basses. One could argue there was a moment, during the first years of the recorder’s revival in the early 20th century, when such a system could have been implemented for our instrument. I’m certainly not the only person to have considered this idea. Evidently some publishers toyed with the idea of taking this route as I have an old Peters edition of a Telemann Sonata which provides recorder parts in both C and F fingering. One can only assume this experiment wasn’t popular and they reverted to the familiar notation we have today.

Sadly this concept didn’t take off, so instead we give our brains extra exercise by learning multiple sets of fingerings. No doubt this flexibility is wonderful in terms of staving off dementia in later life, but it does create the potential for confusion!

Which fingerings should you start with?

For most of my readers this is somewhat academic as you probably already play both C and F instruments. But if you’re new to the recorder, which should you learn first? For children the answer is usually the descant, purely because the instrument’s size better suits small fingers. For adults though, there’s a strong argument for beginning with the treble. The lower tone is more pleasurable when you’re taking your first steps, and ultimately there’s a far wider range of repertoire for solo treble than descant.

Another good reason for beginning with the treble comes when you take your first steps into ensemble playing. More often than not the descant will play the top line, meaning every mistake feels horribly exposed. Playing the treble puts you in the middle of the ensemble - a much more forgiving spot when you’re finding your feet. Any errors will be better hidden and you can build your confidence more easily.

I can play one set of fingerings, why would I want to learn more?

If you’re at the stage where you’re still playing just one set of fingerings, the thought of learning a second set can be daunting. But it’s definitely worth the effort. Playing more than one size of recorder opens up a wider range of music to you and you’ll be welcomed more enthusiastically into ensembles. Yes, you can play descant and tenor without learning different fingerings, but if you’re to count yourself as a truly rounded recorder player you’d be wise to expand your horizons further.

How to get started with a new set of fingerings

If you want to move from C (descant/tenor) fingerings to F (treble) there are books out there which can help. Brian Bonsor’s tutor book, Enjoy the Recorder, comes in varieties for C or F fingerings, but there’s also a ‘From Descant to Treble’ edition. This begins by helping you over that initial bump, as you realise each familiar note now requires a different fingering. Yes, the book was written with children in mind, but it’s packed with lovely tunes and takes a tone which isn’t childish, so it’s just as good for adults to make this step.

If you wish to make the shift from F fingerings (treble) to C (descant/tenor) you’re not quite so well served with books. However, there’s no reason why you can’t learn the new fingerings on your own. The important thing to remember is you’re not actually learning new fingerings. The patterns you use on all sizes of recorder are fundamentally the same. If you play a scale on one recorder then play the same fingerings on a different size of instrument you’ll it’ll sound just as good - just at a different pitch.

So how to get started?

It’s a good idea to learn at least a handful of scale and arpeggios on the recorder you’re already familiar with. Nothing too complicated, but it’ll help if you can associate the combinations of finger patterns with the dots on the page. For instance, here’s a scale of F major for treble recorder. Below it I’ve added a descant/tenor recorder scale which uses the same fingerings - C major.

Play the one on the instrument you’re familiar with, then play its counterpart on the unfamiliar size of recorder. Let your fingers find their way, using the combinations of finger patterns you already know. That was simple enough, wasn’t it?

Play it again, this time consciously associating the notes on the page with the fingerings you’re using. This is easy because you’re used to running up and down scales in the music you already play. For most stepwise note movements you’ll lift a finger to go up and add a finger to go downwards - all very logical. A greater challenge comes when you need to play music which jumps around as you have to move more fingers.

Choose some anchor notes

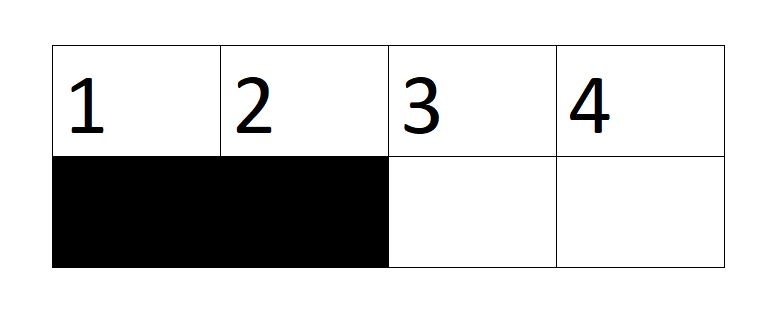

Once you progress past simple stepwise movements it’s helpful to have what I call anchor notes. By this I mean a small selection of notes which you have firmly fixed in your mind and can locate quickly. For instance, the bottom note of your chosen recorder (all fingers covered) would be a sensible choice, as you’ll never need to play any lower than this. Then pick a handful of other notes, scattered through the recorder’s range. These would be my suggested anchor notes for treble and descant recorders:

With a confident knowledge of the fingerings required for these notes, you can then work between them. They give you fixed points on the recorder, between which you can navigate. I guess it’s the musical equivalent of sailors navigating with the help of the stars before the invention of a clock designed to help them track longitude. Faced with an unfamiliar melody line, you can use these to figure out where you start and as familiar landmarks along the way.

For instance, take this section from the melody, Daphne:

The first note is one step above one of our anchor notes, so we immediately know to cover one less finger hole. We then have some stepwise movement, where you can use the scale patterns you already know. The jump to high D takes us one step above another anchor note and then into another scale. These fixed points allow us to navigate our way through the melody accurately, and as you learn what the tune sounds like you’re able to judge whether you’re playing the right notes.

Start with simple material

Using this method you won’t be a particularly quick sight reader initially, so it’s really important to select simple material at first. If you jump straight in with a fast, complex piece you’re much more likely to be disheartened and give up.

Don’t look back!

It might be tempting to keep relating your ‘new’ fingerings back to the ones you’re familiar with. For instance thinking something along the lines of, “This is a G on my descant, so it’ll be a C on my treble”. Effectively you’re transposing everything on the spot. Yes, it might work for slow, simple material, but in the longer term it’ll slow you down because you’re forcing your brain through more processes to find each note. I had a pupil who did exactly this on the treble recorder when he first came to me for lessons. Somehow he’d reached grade 8 standard, but his treble sight reading was abysmal and painfully slow. Over time we worked to help him associate the dots on the page directly with the treble fingerings and his sight reading improved enormously. Yes, the process will be slower at first, but you’ll make quicker progress in the longer term.

Random forays into the wrong fingering

As I mentioned earlier, one of the most frustrating aspects of playing two sets of fingerings is that moment when it all goes wrong. It’s not unusual to randomly play a wrong fingering (for instance a descant fingering on treble or vice versa) for a note or two and then switch back again - sometimes without even realising it’s happened!

This may feel like a random act, but there are common trigger notes, so it’s rarely as random as you think. If you’re aware of these danger spots you’ll be better able to realise when it happens and, ultimately, to try and avoid these errors. These are the most common triggers I see:

Leaps in the music - As we’ve already seen, playing music which moves by step is pretty straightforward because we’re using familiar scale patterns. Leaps are more challenging when you first switch instruments and, as a result, these are the spots where random acts of fingering often happen. Try to be sensitive to this possibility when playing your least familiar size of recorder.

Notes which look like they belong to another instrument - This often applies to high notes. On the treble recorder it’s not uncommon for the music to fly up to two, three or even four leger lines above the stave. If you’re a confident treble player you know this, so when faced with a top C or D on the descant or tenor your brain can unconsciously slip into treble fingering. Equally, low treble notes might subconsciously take you back to the earliest notes you played on the descant or tenor and cause you to play the wrong fingering.

How to spot when you’ve gone off piste

The best way to spot errors in fingering is to listen. For instance, when playing in an ensemble with several players on each part, ask yourself if your notes match those of your neighbour. As Walter Bergmann was fond of saying, “If all the others are wrong and you alone are right, follow the wrong.” This will most often happen when sight reading, or towards the end of a rehearsal when you’re tired and are losing concentration.

Switching to other sizes of recorder

Once you’re fluent in both C and F fingerings you open up a whole world of other possibilities. For instance, the bass recorder uses the same F fingerings as the treble, albeit in bass clef. Playing the bass allows you the chance to be part of the musical foundations in an ensemble and can be very rewarding.

If you’ve ever played another bass clef instrument, adjusting to using your familiar fingerings in bass clef may not cause too many challenges. However, if the clef is totally new to you, I can recommend Mrs McGillivray’s Welcome - a book specifically designed to help you make this switch. It has some useful advice about first steps and is packed full of tunes which progressively expand your range on the bass. Using the same strategy I suggested for the descant/treble switch will work just as well for other bass clef instruments - including the great bass in C.

Venturing further off the beaten track

If you choose to explore more hard core forms of recorder playing, you may be faced with treble recorders in G, voice flutes in D or even more exotic creatures. All of these use the same set of fingerings as your humble descant or treble, but they revolve around a different pitch. For instance the bottom note (all holes covered) of a treble in G is, yes, you’ve guessed it, a G! The voice flute is a tenor recorder sized instrument, but the bottom note is a D instead of C.

For such instruments you could learn to read them as you did with the descant and treble. In practice though, many players (myself included) choose to use tricks to deal with these instruments, especially as they’re used less frequently. For instance, when I play the voice flute (from music in treble clef) I instead pretend the clef is actually a bass clef - as if I’m playing a small bass recorder - and the add three flats to the key signature in my mind. That gets me onto the right fingerings without too much in the way of mental gymnastics and only the accidentals require any adjustment.

There are of course occasions where this doesn’t work. I recently had cause to read a trio sonata with friends which was notated in French Violin Clef. That’s a treble clef which winds around the bottom line of the stave instead of the second line. Effectively, it’s very similar to the bass clef as the bottom line of the stave is G. My usual voice flute trick wouldn’t work because the music was effectively already in bass clef. I could have transposed the music, one note at a time, but my ultimate solution was to imagine I was reading from the alto clef and pretend I was playing a descant recorder! That made my head hurt a little, but it helped us get an idea of the piece was worth exploring further. Once I’d learnt he piece fluently it was no longer an issue.

If you choose to explore viol music you too may encounter C clefs - most likely alto or tenor clef. With these clefs, the centre point of the clef indicates the location of middle C. Often there are tricks you can use to tackle these clefs, much as I do with the voice flute. For instance, tenor clef music can be played on the tenor recorder by reading the dots as if they’re really descant recorder notes!

These examples will be outliers for many recorder players. It may be that you never venture beyond the standard sizes and clefs, and that’s absolutely fine. If you should choose to explore other recorders and clefs just be ready to think laterally to make reading easier.

Practising the switch

Let’s assume you’ve taken that first leap and begun to learn a different set of fingerings or a new clef - how do you practise these new skills?

The most important thing is to do it regularly! As with all new skills, if you don’t nurture them frequently you’ll lose them. This might take the form of practice at home, but don’t overlook ensemble opportunities. If you are a member of a Society of Recorder Players branch (or perhaps a chapter of the American Recorder Society if you live across the pond) take all your recorders with you and switch instruments between pieces of music. Playing with others will help you spot any errors and there’s the comfort of playing with others, many of whom will have been through exactly the same process too.

Switch up the order of your instruments. Don’t get into the habit of always practising your different recorders in the same order when you play at home. Sometimes, change things up - perhaps begin with the treble one day and then select the descant first the following day. This promotes mental flexibility and will develop your ability to play any recorder at will.

Do you have tips and tricks for switching instruments?

If you’ve been playing different sizes of recorder for a while, do you have techniques you find helpful? Maybe you’ve found a surefire way to avoid inadvertent switches, or perhaps you have a great way of reading alto clef? I’d love it if you would share your ideas in the comments below. You may have a method I haven’t considered and it’d be great if we could share our ideas.