Musical notation comes in incredibly varied forms. Most music composed since the mid-19th century contains clear instructions from the composer, showing us where he or she would like us to begin our interpretation. That’s not to say we don’t still have musical choices to make, but generally the music gives us a clear starting point.

Now look back in time. As we travel back through the musical periods, composers give us fewer clues, expecting us to already have sufficient knowledge of the appropriate musical style to be able to make the necessary choices. This can be bewildering – so many decisions to make, but where to begin?!

Handel’s manuscript of his Recorder Sonata in F major

How should we make these decisions?

In an ideal world you’d go back to some original sources, to learn directly from composers and writers of the period. A great starting point for this is On Playing the Flute by Johann Joachim Quantz – a book I’ve talked about before. If you want a glimpse into the 18th century musical mind and an opportunity to pick up lots of helpful tips I strongly recommend you purchase a copy of this iconic book. Quantz helpfully breaks his advice down into user-friendly chunks, so it’s easy to dip in to find the information you need.

For the purposes of this blog post I’m going to concentrate on Baroque music, but many of the same principles can be also used in other repertoire. To illustrate my ideas I’ll use the first two movements of Handel’s Recorder Sonata in F – a piece of music I imagine many of you will already be familiar with. To make life easier, below you’ll find buttons which link to two different editions of this famous sonata.

The first is a facsimile of the sonata from a collection published by John Walsh in London in 1732. The notation is very clear and typical of the type of edition with which Handel’s contemporaries would have been familiar. The music includes only the recorder part and bassline, along with figured bass. Using the bassline and figures the harpsichordist is expected to improvise a performance, allowing complete autonomy over the style and mood of the accompaniment. As a recorder player, being able to see the shape of the bassline is also helpful as you can immediately see the conversation between the two voices.

Secondly, we have a modern edition of the piece, which includes a full realisation of the figured bass – probably the type of edition you’ll be more familiar with.

Taking your first steps on the road to an authentic Baroque style

I’m going to break down the elements of Baroque style, although these inevitably overlap in places. As you gain in confidence and experience you’ll be better able to assess some of these elements ‘on the hoof’, as you sightread. Of course, no one can be expected to form a final interpretation of any piece while sight reading, so don’t worry if at first all you can do is get around the notes and rhythms. As you get to know the music better, try to use some of the self-awareness techniques I discussed in my last blog post to think about the musical possibilities.

Let’s take a look at some of the elements you should think about as you get to know the music better…

Select your tempo

This really needs to be your starting point. Look at the composer’s tempo markings and identify what they mean. If the markings are in a language you don’t speak, go and look them up! Wikipedia has a pretty comprehensive glossary of musical terms here which you might want to bookmark.

Now play the music at what you think is an appropriate speed and consider what mood or character the composer is trying to conjure up. For me, the opening Larghetto of the Handel is quite noble. The lines emerge gradually, building from a simple beginning, blossoming into more expansive shapes later. In contrast, the Allegro is a much livelier, skittish number. It seems to be itching to have some fun at the beginning, with energetic jumps and repetitions, finally leaping properly into action with the semiquavers at bar 6.

Assessing the mood and character this way will influence your choices later. Don’t worry if you can’t play everything in a polished way at this stage – it’s more a matter of deciding what character you want to project, even if technical limitations get in your way at first!

While you’re here, bear in mind what sort of key you’re playing in. Major keys tend to be sunnier and more joyful, while minors are darker and more sonorous. That too may affect the way you decide to play the music, especially if the key changes en-route through the piece.

The implications of time signatures

Now check your time signature. How many beats are there in each bar and how do those beats break down? For instance, a piece in compound time (where the main beats subdivide into three rather than two notes – this sonata’s final 12/8 Allegro for instance) will perhaps have a more rustic, country dance-like feel than a movement in 4/4.

By the time we reach the Baroque period, composers habitually use time signatures to show how the music is constructed – unlike the freer, unbarred music of the Renaissance. In the Baroque style there is a clear sense of hierarchy within the beats of each bar - the first of which is always the strongest. Bear this in mind as you play, as using an equal weight on every beat of each bar will quickly become very repetitive. Try playing the first few bars of the Larghetto with an equal weight on every beat. Then have another go with a gentle emphasis on the first beat of the bar, while making beats 2 and 3 less insistent. Note now this helps the music flow more elegantly.

In time signatures with more beats per bar things become a touch more complex. In four, for instance, you could illustrate the hierarchy of the beats graphically like this…

Beats 1 and 3 are subtly different, but definitely the most important as they begin each half of the bar, with beat 1 being the strongest. Next in the pecking order comes beat 4 – this is because it’s the one that leads us onwards into the next bar. Finally, the runt of the litter is beat 2, the weakest part of the bar. Awareness of this musical hierarchy can help you bring more subtlety to your playing.

Turning notes into musical sentences

Now turn your mind to the phrasing of the music. Compare music to the spoken word. Musical phrases, like spoken sentences need ebb and flow, rather than a continuous, shapeless stream of notes. In text we have punctuation to help us create sense from the words, but in Baroque repertoire we have to figure out the musical sentences for ourselves.

Baroque music is often quite straightforward in its shaping, with phrases tending to come in multiples of 2, 4 or 8 bars – think of it like a poem with a regular number of syllables in each line. With this in mind, look at the music and see if this reveals natural places to breathe. If the music begins with an anacrusis (an upbeat of some sort, perhaps a single beat or half beat note) subsequent phrases will almost certainly follow the same pattern.

For instance in the Larghetto, the recorder part begins with two crotchet beats. If you look at this passage, you can see I’ve added a breath mark before each of these two beat patterns. If you look at one of the scores, you’ll see the bassline also begins many phrases with the same two beat pattern.

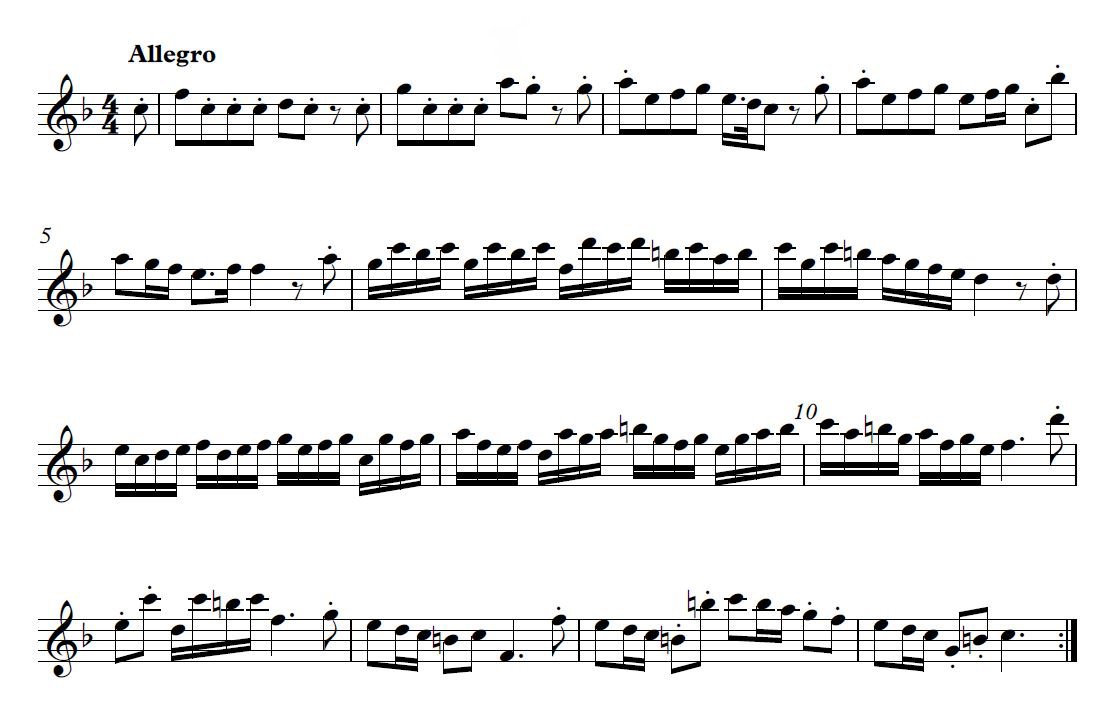

In contrast, the Allegro has a single quaver anacrusis and this pattern also repeats throughout the movement.

All the breath marks in this section come before a quaver upbeat

Naturally, there will be instances where the composer changes things up to add variety, so don’t be afraid to try different approaches and see which you like best. Sometimes the phrasing becomes more obvious when you play the music with its accompaniment – hearing the harmony beneath your line can clarify things.

Adding light and shade through articulation

In modern music we expect composers to tell us precisely how they wish us to articulate their notes, through slurs, staccato, accents and the like. Baroque performers, by contrast, were expected to have an innate understanding of the prevailing musical style and to shape their performances accordingly. Obviously, we can’t travel back in time to talk to 18th century musicians, so this is where resources such as Quantz’s book come in handy. If you listen to older performances of Baroque music you’ll often hear lush, heavy string playing, which owes more to the Romantic period than authentic playing practice.

A lush, romantic interpretation of Bach’s Air from his Third Orchestral Suite by Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic

With the early music revival of the 1960s performers began looking more closely at the practices of the period, introducing greater light and shade into their interpretations, alongside the use of original instruments, or faithful modern copies of period instruments. Much of the variety you find in these performances of Baroque music is created through the use of articulation.

A historically aware performance of the same piece by the Academy of Ancient Music

With a blank canvas to work from (Baroque composers rarely give more than the occasional slur or staccato mark) the possibilities can seem overwhelming. I have a few simple guidelines which I hope will help you come up with your own personal interpretation. I hesitate to call these ‘rules’ as that suggests they are things you must do. Instead, think of them as a starting point and remember too that rules are made to be broken!

Here are the basics ideas I suggest to my students when they’re trying to find a Baroque style, along with some examples from the first two movements of the Handel Sonata:

Slow movements will often be more suited to legato playing than fast ones. But that’s not to say everything should be silky smooth. Try making weaker beats in the bar (see my earlier comments about their hierarchy) a little lighter, and less emphasised to bring in light and shade. Likewise, upbeat notes may want to be lighter/shorter so they don’t become too heavy and distract from the stronger beats.

In fast movements look at the prevailing note values. As a starting point, make the fastest notes mostly smooth (semiquavers in the Handel Allegro), while the second fastest note values (quavers in this case) can be more detached.

The first section of the Handel Allegro with staccato marks to show where I would lighten the quavers. Notice how I choose to play some of the stepwise quavers smoothly.

Now look at the melodic shapes within these detached quaver passages. Leaping notes and repeated notes will often need to be the shortest, while stepwise movement might be better played more smoothly. It’s not a one size fits all rule, but a mere starting point. Notice too, how I use staccato less often on the first beat of the bar, so as to create that sense of hierarchy between the beats.

Be aware of times when the tonality changes between major and minor. A major section may feel absolutely right played in a staccato style, while a similar shape in a minor key might benefit from a more legato approach.

You’ll notice I’ve made no reference to dynamics so far. This is largely because of the recorder’s limited dynamic range. The concept of playing pianissimo or fortissimo is not really relevant to the recorder, but that’s not to say dynamics are impossible. Instead I would suggest you focus more on using a variety of articulation (staccato, legato, accents, slurs) to add variety to your performances.

To add dynamic rise and fall think instead about using the recorder’s natural dynamic range (stronger on high notes, weaker at the bottom) to create a sense of line and shape. For instance, in the sound clip below, the dynamic of the music increases and decreases naturally as the musical line climbs and descends.

To slur or not to slur?

As I’ve already mentioned, few Baroque composers offer much in the way of slurs in their music. Two notable exceptions among recorder composers are Georg Philipp Telemann and Francesco Barsanti. Both were recorder players themselves and therefore knew what best suited the instrument. This means the slurs we encounter in their music work well and can offer ideas we can use elsewhere. For example, here are two snippets by Barsanti and Telemann.

An excerpt from Barsanti’s Sonata in D minor, where he slurs three stepwise notes together within a group of four

In his Sonata in C major, from Der getreue Musik-Meister, Telemann chose to slur groups of six notes together, crossing between neighbouring beats

Sometimes adding slurs into the music can help with faster passages, especially if you’re not yet fluent with double tonguing. A few carefully placed slurs might give your tongue a little breathing space, but I would advise against using them all over the place simply as an excuse not to improve your tonguing!

Instead, look for patterns within the music which might benefit from slurs to add greater variety and interest. For instance, you could use Barsanti’s 1 tongued, 3 slurred articulation pattern, here in the Handel Allegro. Note how the pattern changes to 3 slurred and 1 tongued from the bar 23 to suit the changing melodic shape.

If you choose this route, try to be consistent, adding the same slurs whenever a particular melodic shape appears in the movement. That will bring an added feeling of cohesiveness and make their addition feel like a musical choice rather than something random!

Incidentally, a two notes slurred, two tongued pattern is almost non-existent in Baroque music. It’s much more typical of the Classical period, appearing in music by Mozart and his contemporaries. It may seem an easy choice, but often 3+1 or 1+3 will often be more appropriate, depending on the note patterns you’re playing.

Taking the terror out of trills

The subject of ornamentation can fill an entire book, so I don’t plan to cover it in too much detail here. However, I know trills often strike fear into the hearts of recorder players, especially when your main focus is just getting on top of the notes! However, I’d like to offer a few simple words of advice which may calm your quaking nerves.

What is the purpose of a trill in Baroque music?

In many types of music, trills serve a purely decorative purpose, but in the Baroque they have a different function. You may wonder why teachers and conductors insist on that Baroque trills should start from the upper note. This isn’t just because we’re contrary, but instead it performs an important harmonic function. The whole purpose of a Baroque trill is to create a moment of tension, followed by a feeling of release. The upper note of a trill almost always clashes with the accompanying harmony, creating a discord and a sense of tension. At the moment when your fingers move on, and you begin to wiggle between the two notes of the trill that tension is released.

A strategy for Baroque trills

For many recorder players, trills feel like a distraction, sent to cause them pain and panic. Instead of panicking about their busy-ness I would focus on that upper note. By spending a little longer on the upper note your trills will sound more expressive. It also means you don’t need to wiggle your fingers for quite so long – I think that’s what you call a win-win situation! It’s important to remember that the crucial upper note must begin on the beat and not before. If you start it early (perhaps to try and buy yourself some more time) it’ll be over before the chord it is designed to clash with is played, so the trill loses its entire reason for being.

Finally, don’t feel your trills need to be metronomic and the really fast throughout - this is especially important in slow movements. In slower music you can start to wiggle lazily and gradually wind the speed up. Once again, you reduce the number of wiggles required and your fingers don’t have to move quickly for so long. More importantly, your trills will sound more expressive and musical – another double bonus!

Where next?

I have three parting thoughts which will help you put some of my advice into practice.

The first is to listen to other performers playing Baroque music. Seek out good performers and really listen to how they tackle this repertoire. Ask yourself about the speeds they’ve chosen and where they vary their articulation. How do they phrase the music? How do they create light and shade? Look for performances by respected professional players and remember you don’t just need to focus on recorder music. For instance, listen to the Bach Brandenburg Concertos and note how the string players vary their articulation and phrasing just as recorder players do. Yes, their playing technique is different, but the basics of Baroque style apply to any instrument.

The final movement of Bach’s fourth Brandenburg Concerto. Note how the strings and recorders all vary their articulation to bring the music to life.

Secondly, take risks and experiment! Take a single movement (I would suggest something simple at first) and spend time exploring several different ways to phrase the music. Try the articulation ‘rules’ I’ve suggested then play the music again, breaking the rules. Maybe make copies of your chosen piece and mark them up with different combinations of articulation and phrasing. Do this as many times as you like, but the crucial thing is to be creative and explore all the possibilities. You’ll discover some versions you hate and some you love, but most importantly it’ll get you thinking in a different way. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes – you learn just as much from these as from your successes.

Finally, be bold! I frequently find myself telling students to be more extreme in their creative decisions. It’s too easy to be half hearted in your approach for fear of going over the top and sounding too extreme. In my experience, people are often far too cautious, resulting in bland performances which lack musical interest. Recently I’ve asked pupils to play to me as I listen with a pencil and a copy of their music to hand. As a listener I should be able to understand their intent clearly enough that I can annotate my copy of the music with their phrasing, articulation marks and dynamic shapes simply by listening. You could even record yourself playing and then try this exercise – you might find it very revealing!

I’d love to hear your own tips for creating interesting performances. Or perhaps you’ve been to a concert which really stuck in your memory because it was so dynamic and exciting? What did you learn from the experience and how has it helped you become a better player? Do leave a comment below so we can all share our ideas.

Music making is an endlessly fascinating subject and you can look forward to a lifetime of creative experimentation if you keep an open mind!

Don’t forget, I’m still creating new Recorder Consort Videos, plus regular duets and trios-minus one. Recent additions have included a Fughetta by Glen Shannon, excerpts from Henry Purcell’s The Fairy Queen and a two voice Fantasia by Michael East. You can find all of them over on my Downloads page.