Do you give much consideration to the structure of the music you play? For those of us who aren’t composers, the dark art of writing music can seem a bit of a mystery, but a little understanding will often help us play better. In previous posts I’ve talked about a selection of different musical forms - dances (Renaissance and Baroque), the canzona and sonata and the trio sonata too. While all of these musical forms have a common pattern, there’s another genre of composition which has perhaps the most formal structure - the fugue.

As recorder players we’ll often encounter fugues, whether we recognise them or not. Sometimes they’ll crop up during the course of a piece, and in this situation we often describe the music as being fugal - the composer uses elements of the fugue’s form without writing the complete fugue structure. Of course there are plenty of composers who’ve written formal, standalone fugues - perhaps the most obvious being J.S.Bach. As well as his Well Tempered Klavier (a collection of 48 preludes and fugues - two in every major and minor key) he went even further towards the end of his life, creating a work called The Art of Fugue. This is a collection of fugues, composed during the final decade of Bach’s life. It comprises fourteen fugues (he called them Contrapuncti) and four canons, all in D minor and all based in some way upon a single melodic phrase - truly the pinnacle of Baroque fugue writing and an example for future generations of composers to follow and build upon.

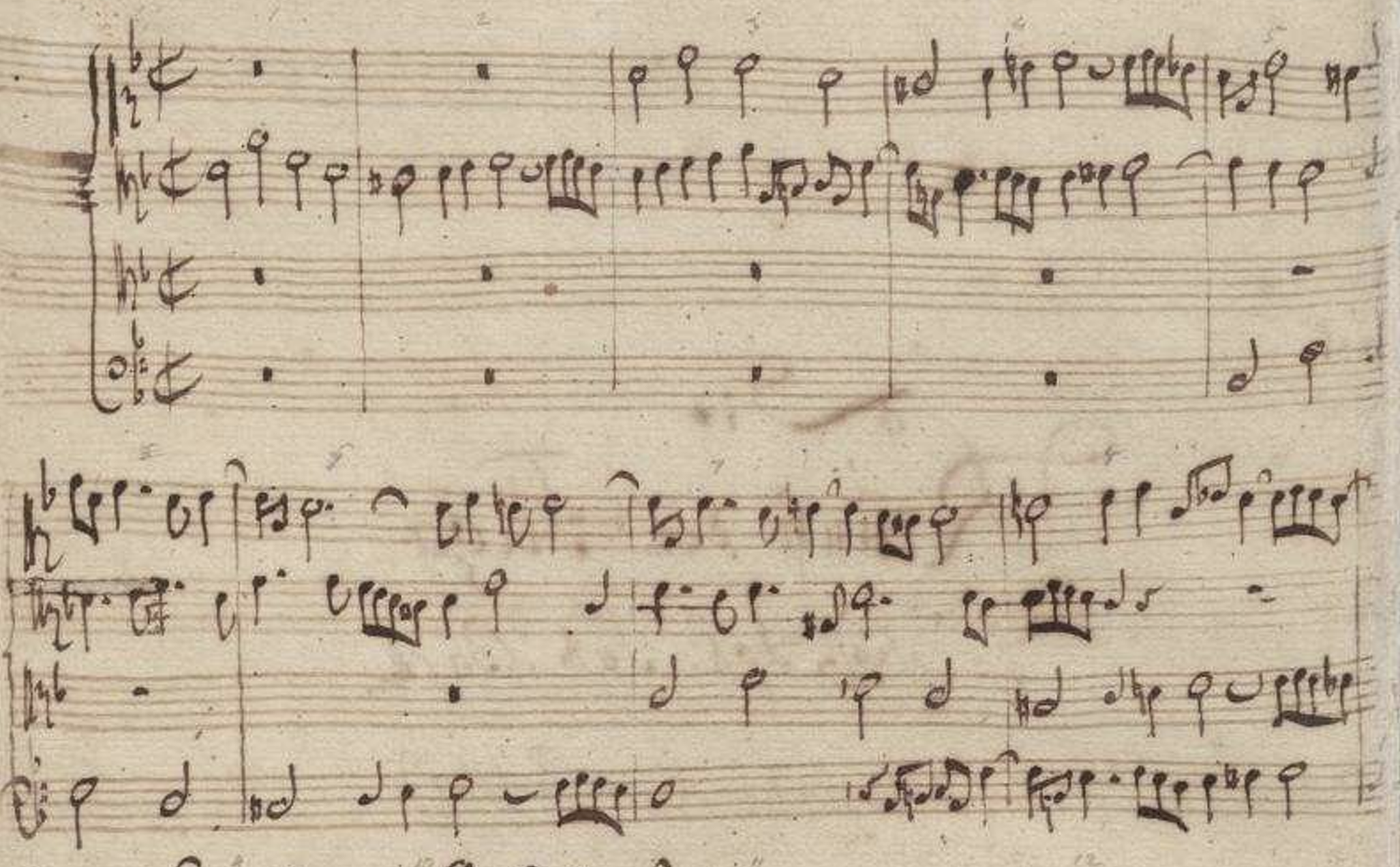

Bach’s handwritten score of The Art of Fugue

As we’ll see, each movement becomes ever more complex. But why did Bach write this magnum opus? Maybe it was the musical equivalent of climbing Mount Everest - simply because he could? Perhaps a more likely reason is it was intended as a didactic work, designed to show others the possibilities of the fugal form.

The final fugue remains unfinished - yet another mystery. There are three possible answers I can see. Perhaps he died while writing, quill in hand? That’s certainly a romantic theory, but probably unlikely. Maybe he purposely left it unfinished so future students could try their hand at finishing the master’s work? Again, this is possible, and dozens of people have done exactly this in the two and half centuries since Bach’s death. If you fancy exploring the infinite possibilities, the Half of the Alphabet blog has collated a list of them, but be prepared to disappear into a vast musical rabbit hole if you start here!

Perhaps the most likely, and most prosaic answer, is that Bach did finish the final fugue, but the last pages have been lost. We’ll look at this theory in more detail later, but at a time when it was far from simple to make a back up of your creations (there were no photocopiers in the 1740s) this strikes me as the most practical reason for its incomplete state.

Which instrument was The Art of Fugue composed for?

This is another conundrum which has had musicians debating for centuries. Bach’s manuscript, and the editions which followed, are laid out in open score (that is a separate line for each voice) rather than the two stave layout we expect for keyboard music today. This has led some to speculate that Bach meant the work to be an intellectual, didactic work rather than one for performance. However, it wasn’t unusual for keyboard players of the period to read from open score, and placing each voice on its own stave also makes the individual melodic shapes much clearer. Modern pianists might find this type of score more challenging to read, but it’s entirely possible to play The Art of Fugue on a keyboard, with two lines being played by each hand.

Of course the open score arrangement has also led many musicians to consider the possibility of performing the Contrapuncti as works for four individual instruments. This has resulted in performances and recordings for almost every conceivable combination of instruments. Woodwind, strings, brass - you name it, it’s been recorded using endless combinations of sounds! This may not have been Bach’s intention, but I like to think he’d have approved of such ingenuity. Some of my favourites include the following:

Amsterdam Loeki Stardust Quartet’s complete recording of The Art of Fugue from 1998. I attended a live performance they gave of this album in the Turner Sims Concert Hall in Southampton and was amazed at their perfect, musicianship, ensemble and tuning.

Rachel Podger with Brecon Baroque - a recording for strings, with added harpsichord continuo. Rachel also took the opportunity to record a short video about the experience of recording this work.

The Swingle Singers jazzy recording of Contrapunctus IX - not one for the purists, but huge fun!

Calefax Reed Quintet - a mixed ensemble of reed instruments, which creates a beautiful contrast of colours in the music.

Aurelia Saxophone Quartet - a sound world which would have been unimaginable to Bach, as the invention of the saxophone was still almost a century away when he composed The Art of Fugue. A fascinating album containing the complete Art of Fugue, plus 15 New Fugues.

A life beyond Bach’s death

Unfortunately Bach died before The Art of Fugue could be published, so that task fell to his son, C.P.E. Bach. He oversaw the engraving of the printing plates, as well as including a number of movements which weren’t part of his father’s original plan. The first edition was published in May 1751, some ten months after Bach died, followed by a second edition in 1752. Sadly the copper engraving plates have long since been lost, but a scan of this edition is available to download from IMSLP. Unusually the engraver chose to make good use of the blank space at the end of several of the Contrapuncti, filling it with elegant engravings of flowers, as you can see below. What a shame modern editors don’t think to make such beautiful use of blank pages today!

A page from the first edition of The Art of Fugue

Let’s go exploring…

Through this blog I’ll use examples from The Art of Fugue to help you understand the structure of a fugue, but later we’ll look at examples from other composers too. I’ve created my own arrangements of eight of the Contrapuncti for you to play. Look out for the black buttons on screen which you can click to download the sheet music. I’ve also chosen recordings of some of the individual Contrapuncti, played on recorders, so you can hear the music as you follow the score. Think of this as a full immersion exploration of the fugues of Bach and others!

But what is a fugue?

Let’s begin at the beginning…

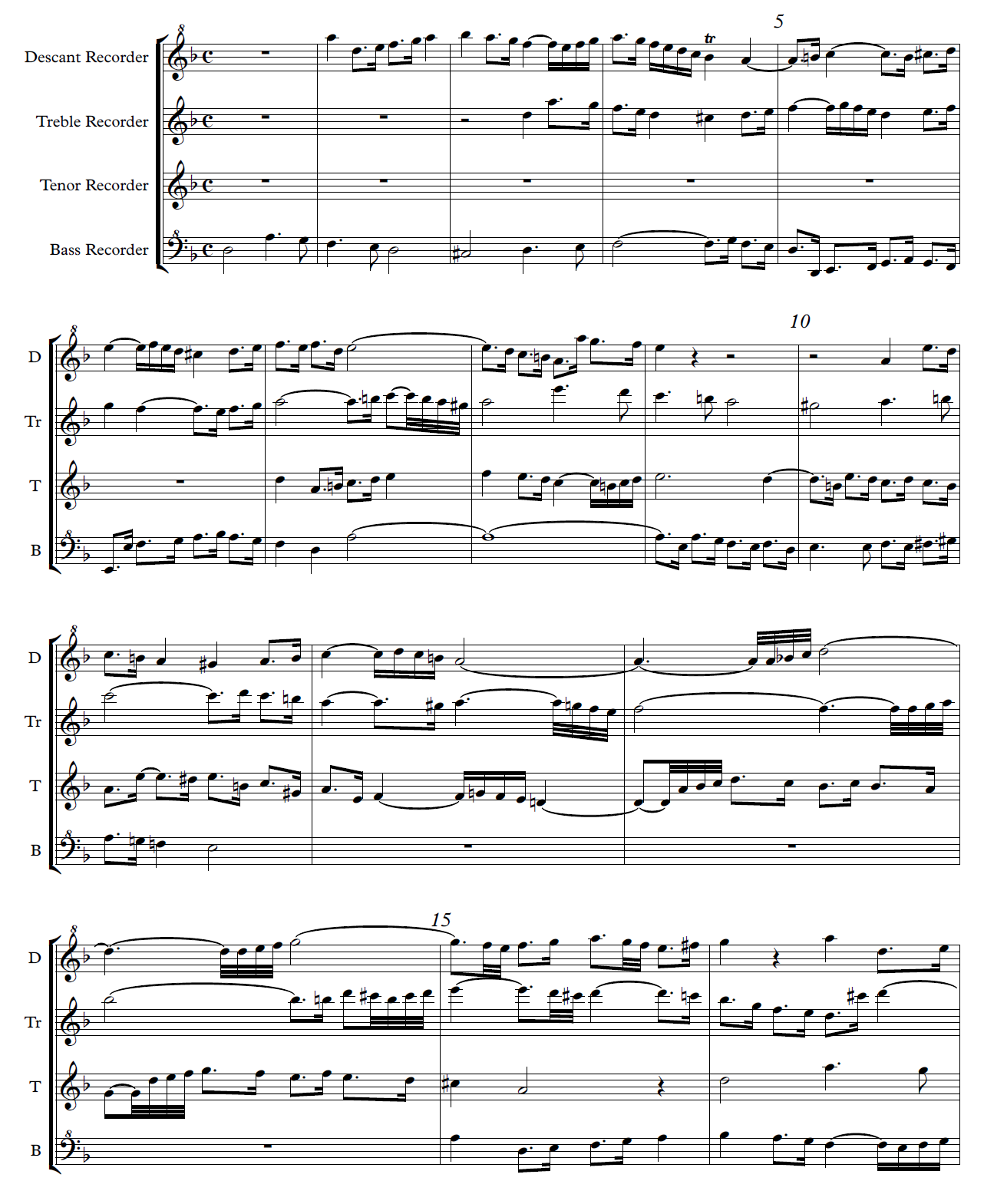

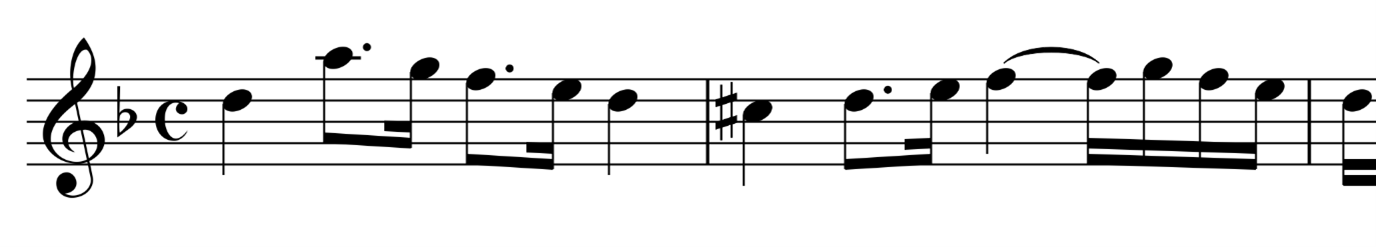

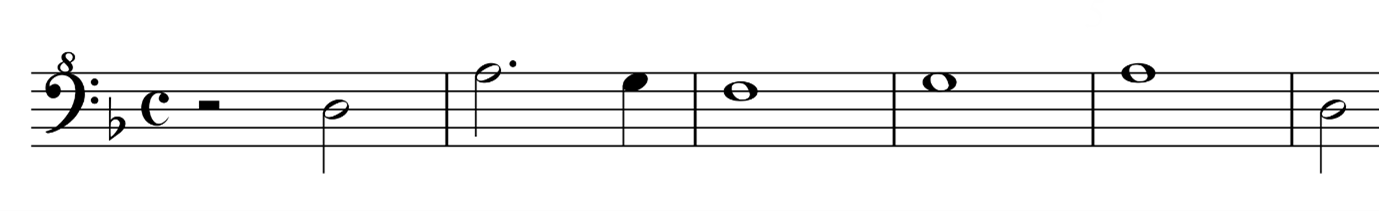

Every fugue starts with a subject – this is the main theme that runs through the work. In The Art of Fugue Bach uses the following idea as his subject and it connects the entire collection of fugues and canons. It’s made from music’s simplest building blocks – an arpeggio and a scale.

The subject on which the whole of The Art of Fugue is based.

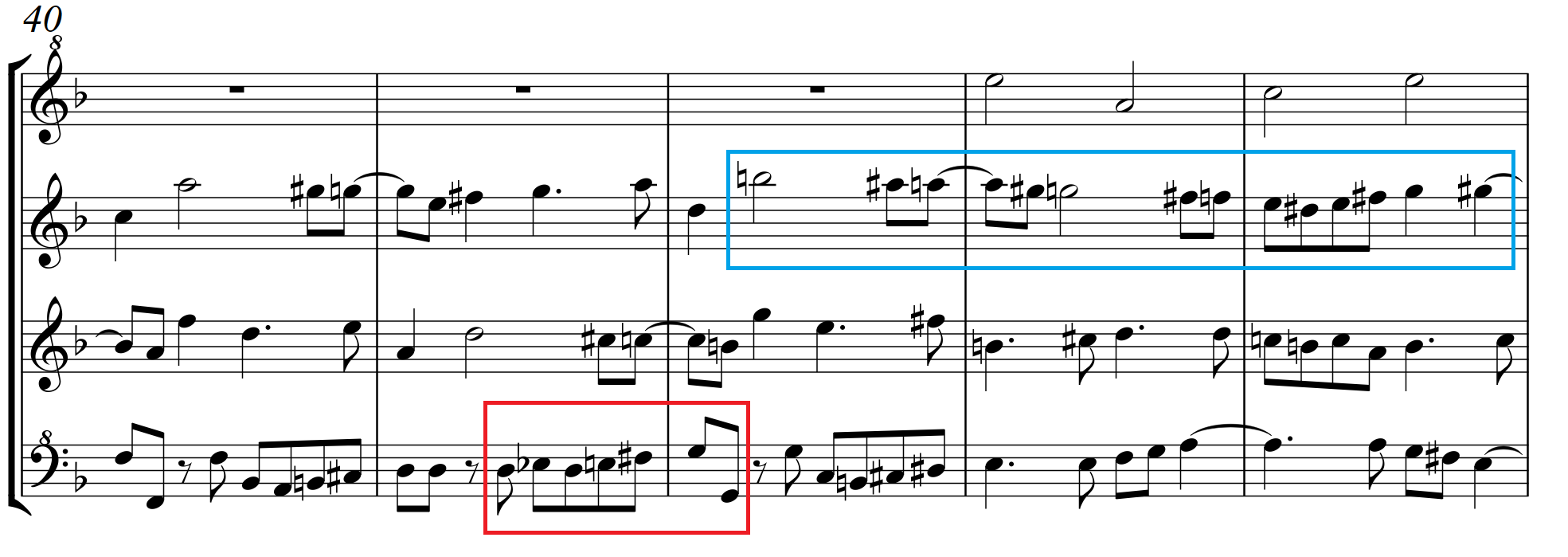

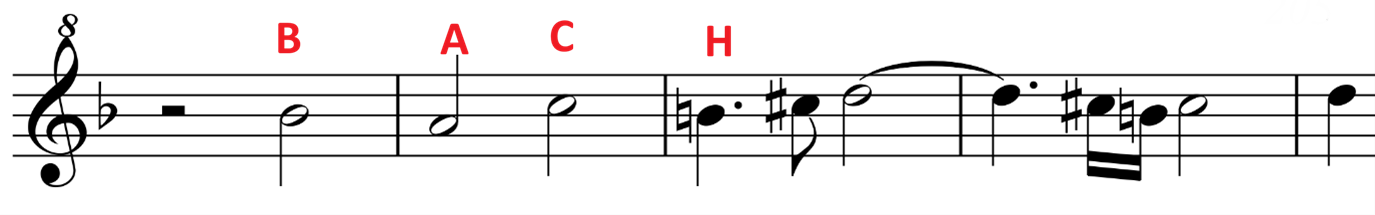

This subject is played by one voice and then imitated by the second voice – this imitation is called the answer. The second voice plays the subject at a different pitch – usually four or five notes higher or lower than the original. If you look at the example (from Contrapunctus I) below, the subject is marked in blue, while the answers are marked in red. See how the second entry of the subject (in the bass part) reverts to the same pitch as the first, while its answer (in the tenor line) is at the same pitch as the first answer in bar 5.

The exposition of Contrapunctus I

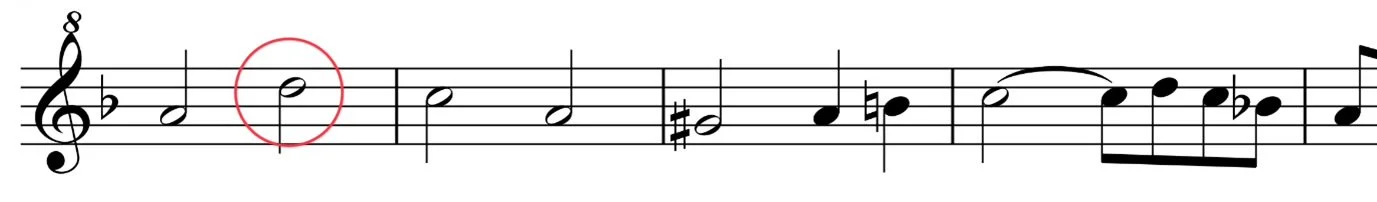

In a fugue there are two types of answer – a real answer and a tonal answer. A real answer is one where the notes follow exactly the same shape as the original. A tonal answer is one where the shape of the phrase has been altered slightly to help it fit with the other lines. In Contrapunctus I Bach uses a tonal answer. If it were a real answer the second note (circled in red below) would need to be an E:

Bach’s tonal answer to the subject in Contrapunctus I

While the second voice is playing this answer, the first voice plays a new musical idea against it. If this music also recurs in other lines it’s called a countersubject. Some composers are very consistent in creating a recurring countersubject, but Bach doesn’t use this technique much in The Art of Fugue.

All of Bach’s fugues in this work have four voices, but there’s nothing to say a fugue can’t have fewer or more voices. The key thing is that each voice begins the piece with the subject. When all the voices have played their first iteration of the subject, we’ve reached the end of the exposition. The example above shows the whole exposition of Contrapunctus I.

What comes next?

After the exposition, the music continues through a series of episodes. These give the composer an opportunity to explore fresh musical ideas, bringing the subject back from time to time.

In Contrapunctus III Bach takes the music in a more colourful direction, with slinky chromatic scales (marked in blue below) and a rising scale pattern (marked in red) which repeatedly appears in the bass line to create a sense of cohesiveness.

Bach’s clever use of chromaticism in Contrapunctus III

Decoration and ornamentation

There’s nothing in the fugal rulebook to say a composer has to keep the subject exactly the same throughout a fugue. While the form has a very clear structure, there’s no reason why the subject can’t be creatively decorated to vary its rhythmic and/or melodic shape. Bach does this often in The Art of Fugue, and Contrapunctus V is a very good example. He uses dotted rhythms to add connecting notes (circled in red in the example below) between the minims, creating a line which has a new shape but is still perceptibly related to the original subject, as you can see here:

Bach’s decorated version of the Art of Fugue subject

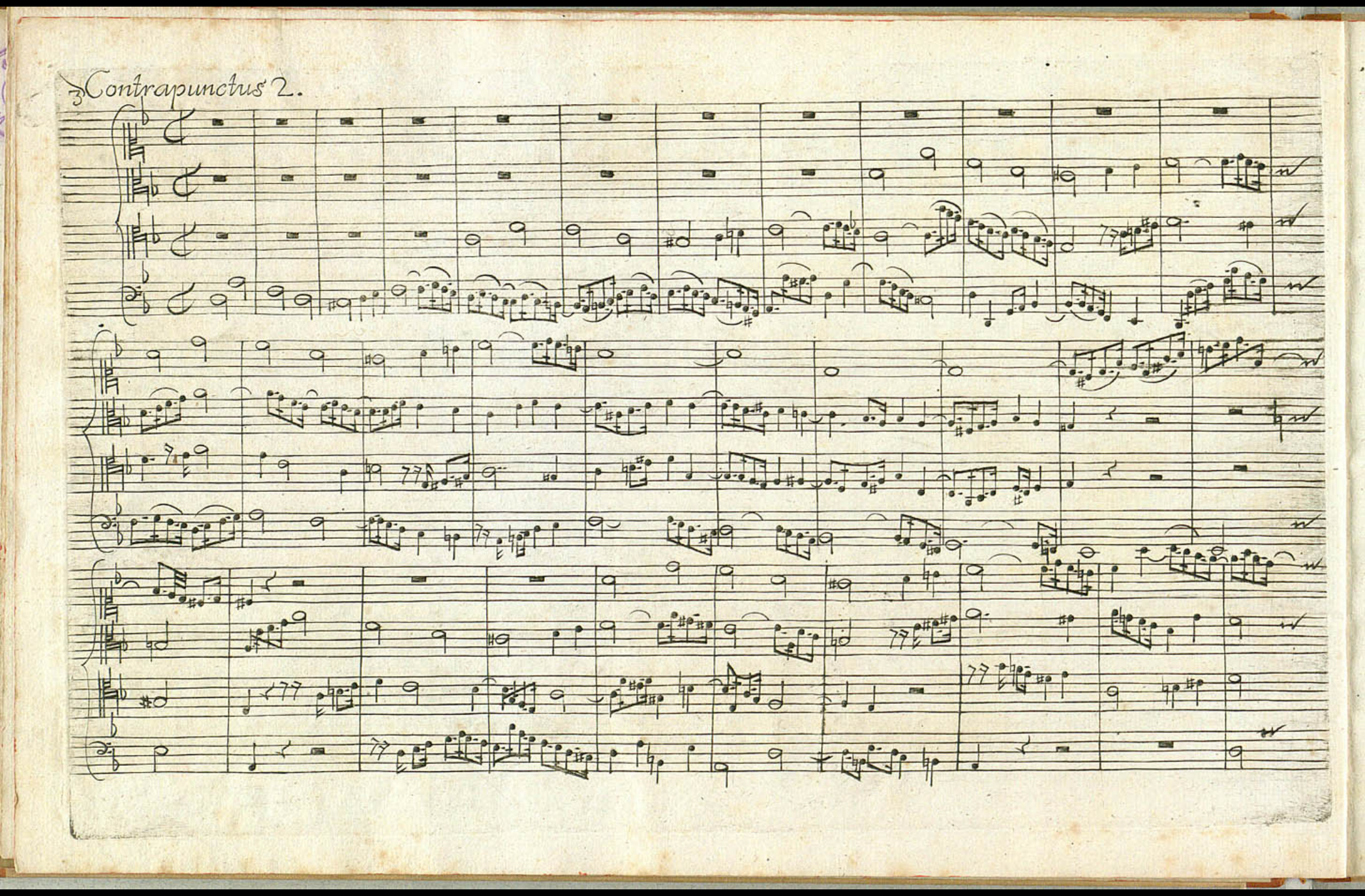

In Contrapunctus II Bach leaves the main subject unadulterated, but instead chooses to have some fun with the melodic lines following its entries. As you can see from this extract from the first published edition, the music is filled with jaunty dotted rhythms interweaving with each other.

Contrapunctus II with its tapestry of dotted rhythms

Exploring different styles from other nations

In Contrapunctus VI Bach looks beyond his native Germany to the style of another country - France. Here he uses more dotted rhythms, along with free flowing runs of faster notes to create the impression of a French Overture. He even labels the movement, In stylo Francese. As you can see from the extract below, it has a much more florid look and style than the other Contrapuncti, and as a result is rather more challenging to play.

Bach also uses Contrapunctus VI to experiment with some mathematical tricks, but we’ll come onto that in more detail shortly.

The opening 16 bars of Contrapunctus VI

Inverted music

Have you ever wondered how a melody might sound if you played it upside down? You’re about to find out, because this exactly what Bach does in Contrapunctus IV!

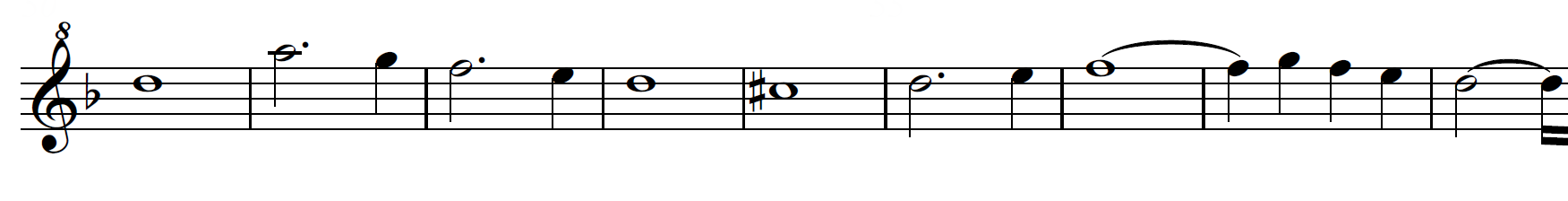

This technique is called Inversion and here the music is literally turned upside down. Intervals (the distance between neighbouring notes) which rise in the original subject will now fall by the same distance, and vice versa. See how the shapes mirror each other in the two examples below. If you have a recorder handy, why not play both versions to hear how inverting the theme changes the sound and feel.

Subject from Contrapunctus I, the right way up…

…and the inverted subject from Contrapunctus IV

Going backwards as well as forwards

You might think Bach used everything from his toolbox when composing The Art of Fugue, but there’s one technique he doesn’t include - that’s Retrograde. This is where a composer flips a theme horizontally, so every note is played in reverse. For instance, a retrograde version of the subject from The Art of Fugue might appear like this:

If Bach had used his theme in retrograde it might have sounded like this….

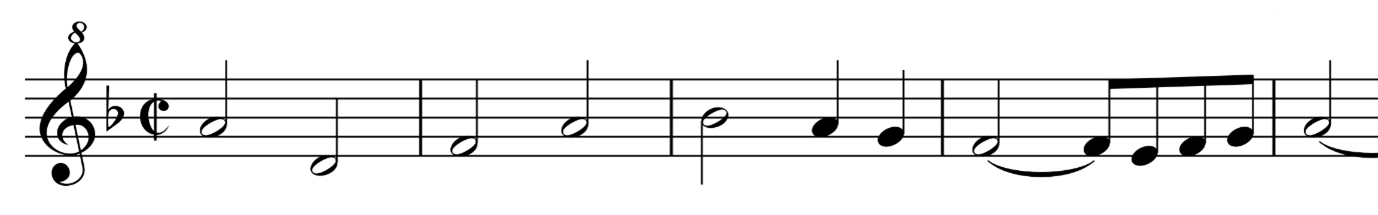

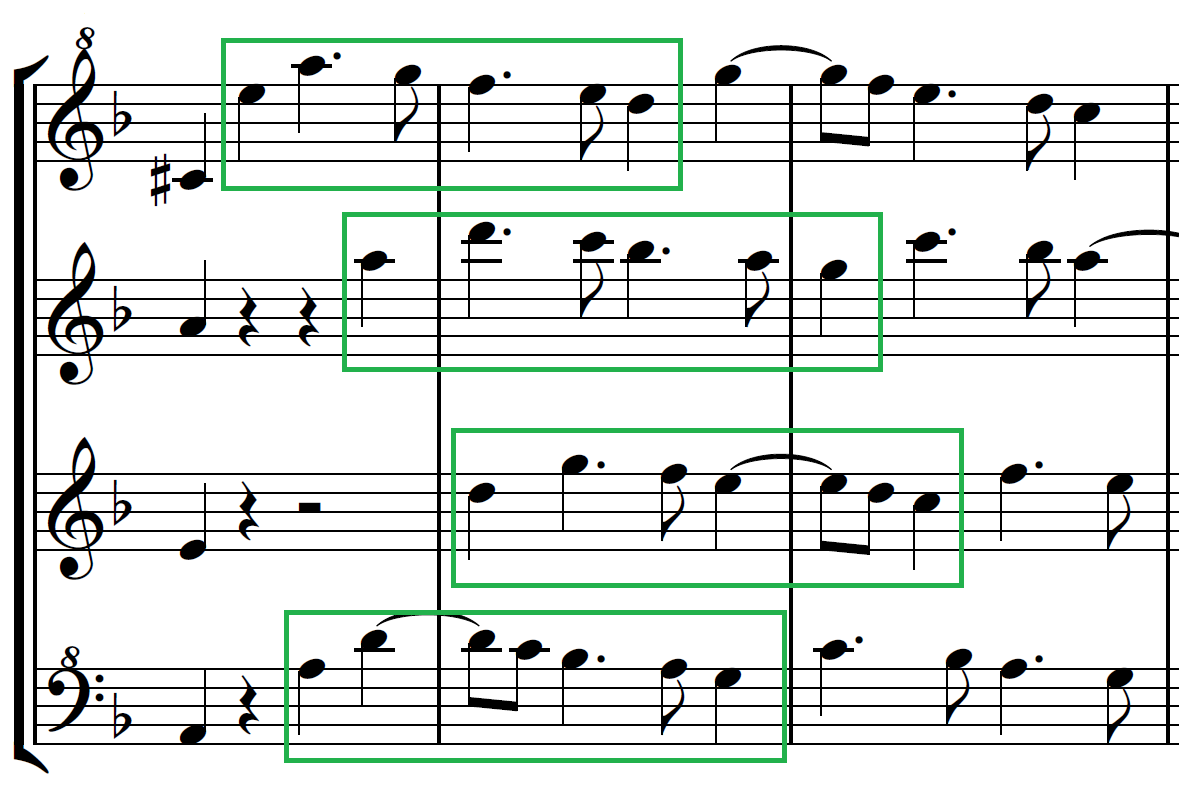

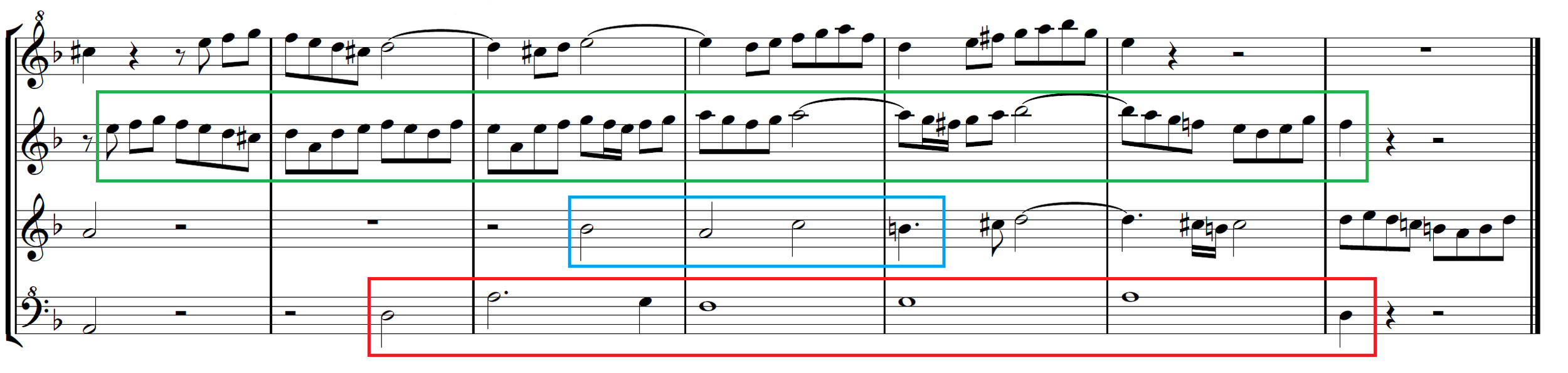

Bach wasn’t a stranger to the concept of retrograde though, writing a Crab Canon in The Musical Offering, BWV1079. This is an earlier collection of canons and fugues, from 1747, which are all based around a theme given to him by Frederick the Great. In the following version of the Crab Canon for recorders (arranged by R.D. Tennent) you’ll see I’ve marked the first two bars in green. Now look at the final two bars of the tenor recorder part and you’ll see red box, which contains exactly the same notes and rhythms but in reverse. If you follow both lines from opposite ends with your fingers you’ll see the contain exactly the same notes and rhythms - so clever!

Why not find a friend to play this with and you can find out how it feels to play the same music in two different directions at once! You can download the PDF sheet music here.

The Crab Canon from The Musical Offering

Playing with rhythm

As I mentioned earlier, Bach sometimes plays with rhythm in his fugues, by extending and contracting the musical lines.

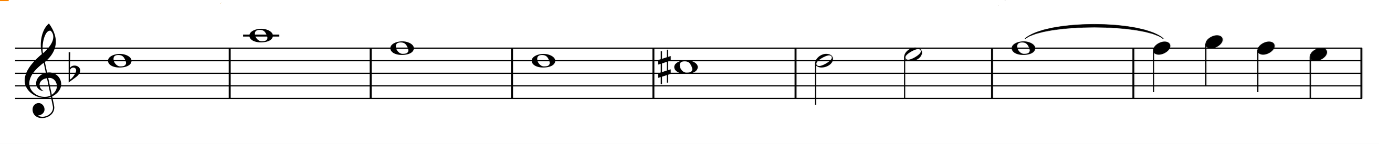

Making the note values longer is a technique called Augmentation. For example, in Contrapunctus IX he includes main subject of The Art of Fugue, but doubles the length of each note. Compare the two extracts below and you’ll see how each note is twice as long as the original.

Original theme

Augmented theme from Contrapunctus IX

In contrast, Diminution does the opposite, making the note values shorter.

You remember I earlier showed you the decorated theme Bach uses in Contrapunctus V? Not content with simply ornamenting his musical idea, in both Contrapunctus VI and Contrapunctus VII he uses that decorated version in both diminution and augmentation. Not only that, he does this with the theme the right way up, and in its inverted form!

This is the decorated theme:

Compare that with the version in diminution - all the same notes, but half the length:

And finally, the same musical idea in augmentation:

Cranking up the excitement

As a fugue progresses, composers often look for a way to crank up the energy and excitement. One way to do this is Stretto – a technique where the main subject is repeated in a second voice before it has finished playing in the first. These closely packed entries create a sense of greater urgency and tension. In Contrapunctus V Bach does exactly this, writing entries of the decorated subject just two beats apart from each other. To add to the complexity, one of them is the right way up (shown with a red box below), while the other is inverted (in a blue box).

If you want an even more extreme form of stretto, that can also be found in Contrapunctus V. In this extract, he uses just the first few notes of the decorated theme in all four voices, with just one beat between each entry, as you can see with the green boxes below.

Double fugues - twice the fun!

What could be more exciting than a fugue with a single subject? A fugue with two different subjects, of course! Unsurprisingly this is called a Double Fugue, and Bach uses this trick several times in The Art of Fugue.

His first experiment with this appears in Contrapunctus IX, which begins with an entirely new, and altogether more energetic idea:

The new subject for Contrapunctus IX

The movement begins with what seems like a fugue based entirely on this new theme, but he has a surprise waiting in the wings. At bar 35, after all four voices have played this new subject he reintroduces the original subject, from Contrapunctus I, but this time in augmentation, as I mentioned earlier:

From here to the end, every time the busy subject appears it’s accompanied in parallel by the main Art of Fugue subject.

Not content with writing one double fugue, Bach continues with this strategy in Contrapunctus X, although his new musical idea is more fragmented than the one from Contrapunctus IX. Again, he uses it the right way up and in inversion, before reminding us of the decorated version of the main Art of Fugue subject at bar 23. Finally, at bar 44 he brings the two together, as you can see in the full score (which can be downloaded by clicking the button below).

The rather fragmented subject in Contrapunctus X

The grand finale

As if double fugues weren’t impressive enough, Bach brings The Art of Fugue to a climax with a Triple Fugue for Contrapunctus XIV. As you might imagine, this brings together three different, new subjects.

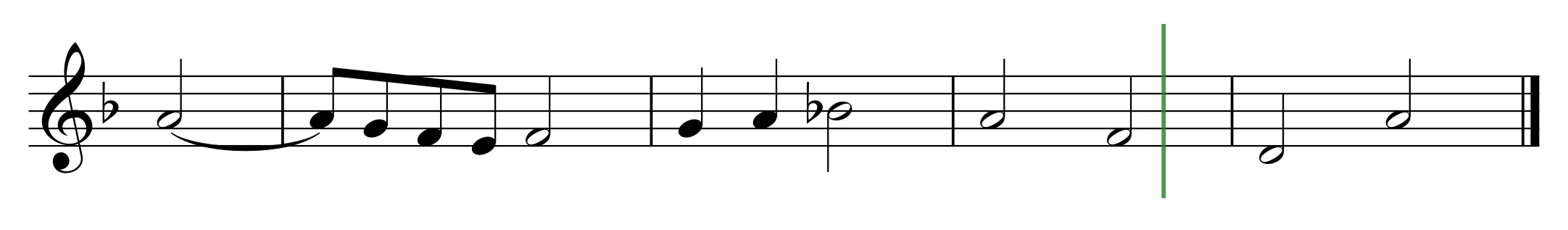

The first subject shares some genetic material with the original, used in Contrapunctus I, but is more static and provides a calm, thoughtful start to the fugue:

Subject No.1 from Contrapunctus XIV

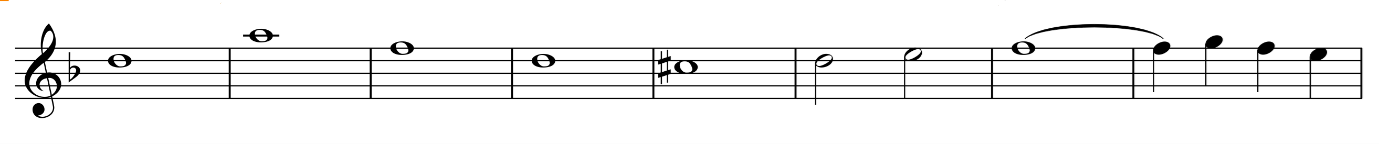

The second subject has a more fluid feel, with running quavers. It’s also the longest subject, running for almost seven full bars:

Subject No.2 from Contrapunctus XIV

For the final subject Bach takes an autobiographical turn, converting his name into music. In German the note B natural is indicated by the letter H, so the name BACH is spelt out by the first four notes of the subject. Other composers have also used the same technique. For instance, Dmitri Shostakovich used DSCH as a musical motif D-E flat-C-B natural in several of his works.

Subject No.3 from Contrapunctus XIV

In the final few bars Bach finally brings all three subjects together for the first time. The extract below shows this meeting of ideas, with the 1st subject in red, the 2nd in green and the 3rd BACH theme in blue.

Before we get to see more of how these three ideas will work together, the music stops abruptly at bar 239. It may be that Bach originally intended it to become a quadruple fugue, bringing the original subject back, combined with the others, but his true intentions remain a tantalising mystery!

The final few bars of Contrapunctus XIV, where all three subjects coalesce.

It’s not all about Bach…

While you could argue that Bach is the master of the fugue structure, he’s far from the only composer to have written such works. I’m now going to point you to some works by other composers to listen to. Several of them have appeared among my online consort videos over the years, so for those you’ll see buttons which will whisk you over to the download folder, so you can play along with me if you want to.

The roots of the fugue

The concept of imitation wasn’t a new one when Bach started composing fugues - composers had been writing imitative music for many years. Canzon Seconda by Giovanni Gabrieli begins with strict imitation between all four voices. Composed more than a century before Bach wrote The Art of Fugue, it doesn’t yet follow the precise format of a fugue, but you can see its genetic connection to the Baroque fugue.

Bach’s hero

At the age of 20 Bach walked nearly 400 kilometres to meet his hero, Dietrich Buxtehude, and hear him play the organ, so you won’t be surprised to learn that he too wrote fugues. This Organ Fugue in G (you can download the score here to follow along) also uses one of the techniques favoured by Bach in The Art of Fugue, inverting the main theme for the middle section, from bar 19, before returning to its original form for the final section at bar 39.

Beethoven’s counterpoint teacher

Johann Georg Albrechtsberger is best known today as the person who taught counterpoint and fugue writing to the young Beethoven, so it’s no surprise to find he wrote a large number of fugues himself. The subject of this Organ Fugue is really quite simple - just seven notes - but he is still able to create a satisfying fugue from them.

Following in the footsteps of his teacher…

Albrechtsberger was evidently an effective teacher, as Beethoven went on to write powerful fugues in many of his works, including several of his symphonies. His fugal efforts culminated in the Grosse Fuge, Op.133, composed in 1825 and originally intended to be the finale of his 13th String Quartet. By this stage, just two years before his death, Beethoven was profoundly deaf and this disability led him to write some extraordinarily forward thinking and very demanding music. Ultimately his publisher insisted on a different finale for the Quartet, so as not to harm sales of the sheet music, and the Grosse Fuge became a standalone work. It’s an immense double fugue lasting some fifteen minutes and not an easy piece to understand. The video below includes the score on screen so you can follow along to the music as you listen.

The fugue as part of a bigger picture

As I mentioned earlier, fugues don’t have to be standalone works and composers often include fugal sections within larger works. Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus (from Messiah), for instance, begins as a joyful chorus in block harmony, but then introduces a series of fugal entries from bar 41. This doesn’t progress into a full blown fugue, but the subject returns again at the end of bar 71 against the other musical ideas.

Mozart’s foray into the double fugue

I’ve mentioned Beethoven’s double fugue writing already, but there are many more by other composers. One of the best known is the Kyrie from Mozart’s Requiem, which contains two contrasting subjects. You can play along with my consort video, but here is one of my favourite recordings too, which I think captures the full operatic drama of the music.

Fugues in every key

Bach wasn’t the only composer to explore the possibilities of writing fugues in every key - Dmitri Shostakovich also composed a Prelude and Fugue in each major and minor key, inspired by and dedicated to the pianist Tatiana Nicolayeva, during 1950 and 51. No.4 in E minor is a powerful double fugue, played here by Vladimir Ashkenazy. If you’d like to follow the score as you listen you can download it from IMSLP here (page 27). The second subject first appears at the Piu mosso section, and Shostakovich brings the two themes together from the last five bars of page 30.

A devil of a fugue

To complete my round up of amazing fugues, we have a truly astonishing fugue contained within a brass band piece by Derek Bourgeois - The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Composed in 1992 as a test piece for the final of the National Brass Band Championships at the Royal Albert Hall, it builds into a truly virtuosic fugue. This was inspired by Edward Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Strings, which includes (in Elgar’s own words) “a devil of a fugue”. The subject Bourgeois writes is one of the most expansive I’ve ever encountered, covering some seven bars and dozens of bustling semiquavers, followed by a tour de force of fugal writing.

The fugue (you can see the score here) begins at bar 119 and it’s still going strong a hundred bars later when Bourgeois brings the subject back in the trombones, tubas and timpani at half speed! The entire work last some 17 minutes and I recommend listening to the whole piece, but if you want to skip straight to the fugue, you’ll find it 5 minutes and 10 seconds into the recording below. Bear in mind that this is a performance by a band of amateur musicians - genuinely awe inspiring!

A surfeit of fugues?

If I haven’t already overwhelmed you with fugues, I have one final recommendation, and that’s an episode of BBC Radio 3’s Early Music Show from 2014 about The Art of Fugue. Presented by the late Lucie Skeaping, it also features Simon Heighes, one of my history of music professors at Trinity College of Music, who talks about this magnum opus in a very informative and user friendly way.

I realise this post has been something of a fugal marathon but, as you will now realise, the fugue is an immense subject!

Even if you don’t think you’ll ever listen to fugues purely for pleasure (I know some find them a little too esoteric) I hope I’ve opened your eyes and ears to the special way they organise themes and can create a tremendous sense of excitement and drive. Hopefully you’ll more easily recognise a fugue when you encounter one in future and perhaps appreciate the huge skill required by Bach and other composers to bring the themes together to create a satisfying whole.

Have I missed out a fugue you particularly enjoy? I’d love to hear your thoughts on the topic and perhaps your recommendations from this tremendously broad field - please do leave a comment below to tell us about your favourites!