Do you panic when you see a trill sign in your music? Does the thought of all those fast notes send you into a frenzy? If so, you’re not alone! It’s amazing that something so small and so frequent in the music we play can cause so much worry, but I’m here today to help you overcome your fears. With a little thought, time and practice your trills can become a thing of elegant beauty rather than sheer terror.

What is a trill?

Fundamentally a trill is an ornament – a decorative addition to the music. At its most basic level, a trill is a rapid oscillation between the printed note and a pitch one step higher. It’s important to take the key signature into account, so you play your trills within the key of the music you’re playing. Therefore, in a piece with no key signature if your printed note is an A, you will alternate between that and a B. On the other hand, if your music has a key signature of one flat your upper note will be a B flat.

For the purposes of this blog post I’m going to focus on Baroque trills, as this is the type of repertoire where you’re most likely to encounter them. There are subtle differences to the way you play trills in earlier and later music – for instance whether you begin on the upper or lower note – but if you start with a sound understanding of the Baroque variety you’ll be in a good position to explore these later.

Let’s start by taking a look at the practicalities of trills – the hows, whys and whens. Then I’ll help you build up your skills so your trills can sound effortlessly elegant.

What is the purpose of a Baroque trill?

I said earlier that a trill is an ornament. This suggests it has a purely decorative function – like a porcelain figurine sitting on a shelf. In some music this is true, but Baroque trills have a more specific purpose – to create a sense of tension and release. In order to understand this we first need to know where to begin our trills.

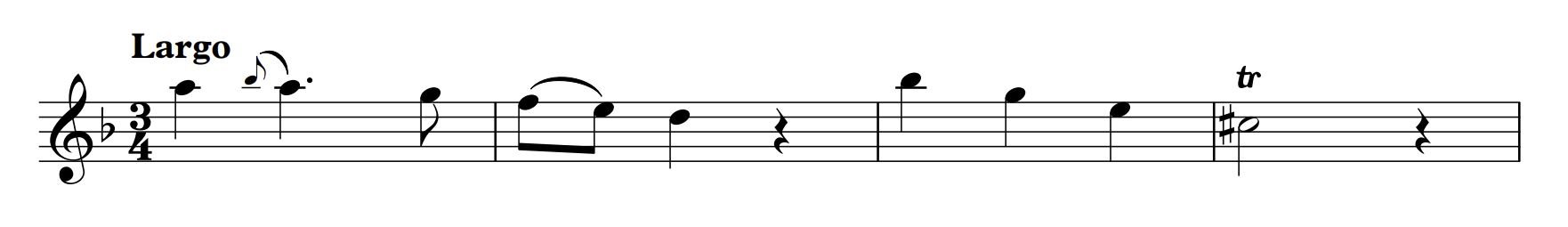

You already know that a trill is made up of two pitches – the one notated in your music and the note immediately above. Which should you start on? Put simply, it’s almost always the upper note. So when playing the following phrase (from Telemann’s Sonata in F) you would begin the trill in bar 4 on a D and then alternate swiftly between that and the notated C sharp.

But why do we begin trills on the upper note?

This is where the concept of tension and release comes into play. Take a look at the same passage again, shown this time with the accompaniment.

If you study the chord beneath the trill in bar 4 you’ll see a chord which includes an E and a C sharp. By playing the upper note of the trill (a D) against this you create a discord or clash in the harmony. This creates a sense of tension, which then dissipates when the trill resolves downwards to the C sharp. This is the purpose of a Baroque trill. No doubt you’ll have heard teachers and conductors nagging to begin trills on the upper note – now you know why. It’s not because we’re trying to make life harder for you, but instead to create that magic combination of tension and release.

Where should I play a trill?

If you’ve played a reasonable amount of Baroque music you’ll have encountered places where your teacher or conductor tells you to insert a trill, even though it’s not marked in the music. Why is this? Is the composer being lazy in his or her notation?

Not at all! We’re spoilt with modern notation – composers today generally give very clear information about the way they’d like the music to be played. It’s not unusual to have very detailed articulation marks (slurs, staccato, accents and the like), dynamics and even the odd trill printed into our music. With early music (generally prior to around 1750) composers left these creative decisions in the hands of the performer. Because players were familiar with the style of the period they knew what was expected of them so there was simply no need to mark every last little detail in. This requires a lot of decision making on our part – a topic I talked about in an earlier blog post which you can find here.

When it comes to trills, the most common place for them is at a cadence point. A cadence occurs at the end of a phrase, usually accompanied by a particular combination of chords. Whether you have a knowledge of harmony or not, these chord progressions are so much a familiar part of the music that you’ll probably have an instinctive sense that you’re reaching the end of a musical sentence. At these points a trill will often be added to the penultimate note of the phrase, emphasising this point. For instance, listen to Dan Laurin’s performance of the opening movement of Handel’s Sonata in C. Note the way his trills occur just before the end of phrases. These are points where there is a moment of repose, before the music moves onwards. Think of it like the time you would take at punctuation points if you were reading a piece of prose aloud to an audience.

Sometimes these cadential trills will be notated in the music – perhaps by the composer, or as additions from the editor. There will be lots of other places where a trill might be appropriate though, so don’t be afraid to try putting them in. If you feel you’re approaching the end of a musical sentence pop in a trill and see if it works. What’s the worst that can happen? You might find it fits perfectly and, if not, you can try somewhere else next time. No one will suffer an injury from an incorrectly placed trill!

Which notes should I articulate?

With potentially lots of notes to play you may be daunted by the thought of getting your tongue around them. Fear not! Baroque trills are always slurred so you should tongue the first (upper) note and then your tongue doesn’t need to make contact with your hard palate again until the note immediately after the trill. It’s very easy to slither onto this final note in an uncontrolled way. This may be because you find it hard to coordinate your tongue with this single note. If this is the case, instead focus on the underlying rhythm beneath the trill. Let’s look at an extended extract of the Telemann again:

Take a look at the rhythm of the trill in bar 7 - a dotted crotchet followed by a quaver. You wouldn’t think twice about tonguing those two notes cleanly without the presence of the trill. Instead of worrying about how you’re going to coordinate your tongue stroke with that quaver, focus your articulation on the underlying rhythm as though the trill wasn’t there at all. Once your trill finger patterns have a little more control you’ll find they match up very easily. I’ll talk a little more about creating shapely trills in a moment.

Selecting your trill fingerings

This is an occasion when Occam’s Razor should come into play – a centuries old principle which decrees that the simplest answer is usually the right one. In other words, if you can play your trill by using the standard fingering for both notes, you should do exactly that! There will of course be some combinations of notes where this isn’t possible – for instance the trill which appears in bar 6 of the example above (the equivalent trill would be C to B on a descant or tenor recorder). Here it isn’t practical to shift cleanly and swiftly between the two standard fingerings so an alternative has to be used.

A very thorough chart, showing trill fingerings for all sizes of recorder, can be found on the Dolmetsch website here. You could perhaps print out a copy and keep it near your music stand or in your recorder case for reference.

Feeling overwhelmed at the number of possible trill fingerings? Don’t be!

Recorder music tends to be written in a fairly limited number of keys. This means the number of trill fingerings you’ll need on a regular basis is relatively small. If you’re just starting out with trills, get to know a couple to start with and use them whenever they occur in your music. Once you’re comfortable finding one or two of these in the heat of the moment, choose another one and add that to your repertoire. There’s really no need to bamboozle yourself with all of them at once – instead add new trill fingerings gradually and they’ll stick in your muscle memory more easily.

Making your trills shapely

It’s all very well knowing the theory of playing trills but the next step is making them feel like an integrated part of the music. Johann Joachim Quantz offers his thoughts on this subject in his 1752 book, On Playing the Flute:

“Shakes [trills] add great lustre to one’s playing, and, like appoggiaturas, are quite indispensable. If an instrumentalist or singer were to possess all the skill required by good taste in performance, and yet could not strike good shakes, this total art would be incomplete.”

If trills set you into a state of panic it’s easy to forget about ‘good taste’, instead throwing your fingers at them and ending up in a frantic mess. Take a moment to remember what I said earlier about the purpose of a Baroque trill. In music of this period trills are an expressive device, as much an a decorative one. Therefore you’ll achieve a more stylish result if you focus more on the shape of the trill and less on the sheer speed required.

Remember, the upper note of the trill is the moment where you create a discord – that moment of tension. This note is an appoggiatura - the Italian word for a leaning note. Sometimes the composer or editor will print this appoggiatura in the music (see bar 1 of the Telemann example above) but even if they don’t, you still need to play it. The longer you can spend on this appoggiatura, the more expressive the result. Not only that, but by lengthening the upper note you reduce the time remaining and therefore the number of wiggles you need to fit in. The result – a more expressive trill that sounds more musical and is easier too. I call that a win! Listen to these two snippets of me playing a short section from the Handel C major Sonata – the first with fast trills which have a short upper note, the second with longer, more expressive appoggiaturas. Do you agree that the second feels more stylish and expressive?

Speed isn’t everything

My harpsichord teacher, Maria Boxall, often used to remind me that trills don’t need to be like wallpaper. Imagine of a roll of wall paper – the printed pattern repeats at the same interval throughout its length. This is the wall paper equivalent of a fast, whizzy trill. Now imagine instead a roll of paper where the repetition of the pattern alters along its length. At the top of the roll the patterns are distanced from each other and their repetition increases in frequency as you move down the length of paper. This is a great image to have in mind as you begin a longer trill. You don’t need to jump in feet first, at full speed. Instead, start the oscillation slowly and gradually wind it up. See how much more shapely this makes it feel? I’ll give you some exercises to practise this later.

Again, Quantz has some good advice on this subject:

“All shakes do not have to be struck with the same speed; in this matter you must be governed by the place in which you are playing, as well as by the piece to be performed. …. In melancholy pieces the shake must be struck more slowly, in gay ones, more quickly.”

As Quantz suggests, you should always consider the mood and character of the piece you’re playing. A fast, energetic movement may demand swift, snappy trills, whereas in a slow movement a more leisurely approach might feel more appropriate. Again, here are two snippets from Handel’s C major Sonata – one a sonorous Larghetto, the second an energetic Allegro – notice how I tailor the character of the trills to match the mood of the music.

How do I finish a trill?

Now you have a better understanding about the way trills begin we need to consider how to finish them. Quantz offers this advice:

“The ending of each shake [trill] consists of two little notes which follow the notes of the shake, and are added to it at the same speed. They are called the termination. This termination is sometimes written out with separate notes. If, however, only a plain note is found, both the appoggiatura and termination are implied, since without them the shake would be neither complete not sufficiently brilliant.”

However, later he does later add:

“I would like to note in addition that if shakes are indicated above several quick notes, the appoggiatura and termination are not always possible because of the lack of time.”

So it would seem it’s case of “You should always play trills the way I specifiy, except on occasions when it’s not practical” - a wonderfully pragmatic approach!

Another option for finishing trills is to use an anticipation note - a brief anticipation of the note you finally land upon. In the first movement of Telemann’s Recorder Sonata in C we see him writing these anticipation notes into the music after the trills (notated here with a + sign rather than tr).

It’s worth practising these different endings for trills so you can call upon whichever is most appropriate in the heat of the moment. In Gudrun Heyen’s Advanced Recorder Technique, Volume 1, she offers these patterns as the basis for practising anticipation notes or turns at the end of trills. The three patterns are shown for a trill on a C, but you could replicate the pattern and practise is on any note to acquire the muscle memory for any key.

Developing your trill technique

One of the things people worry about most with trills is the sheer speed. As we’ve learnt, trills don’t always need to be super-speedy, but there will be occasions when you need some velocity. For those moments it’s important to hone your finger movements and practise them so you can call upon that speed when necessary.

Let’s begin with this simple exercise:

Begin with a steady tempo - maybe crotchet = 72. As you play, focus on the quality of your finger movements. You should keep your fingers as relaxed as possible, using as little effort to seal the finger holes as is absolutely necessary. Make your finger movements small too – don’t lift your fingers more than about a centimetre above the holes. Remember – the further you lift your fingers, the longer they will take to come back down again. You may find it helpful to play these exercises in front of a mirror so you can see your fingers from a different perspective.

Now focus on the evenness of your notes. Close your eyes and really listen. Taking away the visual element makes you listen more carefully. Remember, lifting a finger takes just a fraction more effort than lowering it as you are working against gravity.

Now do the same exercise on different notes, working up from the bottom of your recorder. Some fingers will move more easily than others – third fingers are often recalcitrant and moving your thumb quickly may prove troublesome too. This is because the joints in our thumbs work in a different way to those in our fingers because they have a greater range of all round movement. Once you can do this exercise on every note at this slow tempo, gradually increase the speed of your metronome to make your fingers move faster.

Spend a few minutes on these patterns each time you practise and you’ll soon find you gain speed and flexibility.

Now for some rubato…

OK, so you’ve got your fingers moving more quickly. Now we need to introduce the flexibility needed to create a shapely Baroque trill. Here we use rubato. This Italian word means robbed time – literally you’re stealing time from some notes and adding it to others to create a feeling of flexibility and spontaneity.

Now take the exercise we did just now, oscillating between two notes, but instead of precise, mathematical changes in tempo go for a gradual increase of speed. Begin really slowly and gradually move your finger faster until you reach your terminal velocity. Again, with some finger combinations you may find you get stuck, as a finger momentarily stalls. Keep trying, but be careful to maintain the feeling of relaxation in your digits. Tension is your greatest enemy when it comes to developing speed. While you’re at it, try the same exercise with trills which gradually reduce in speed, and finally trills which increase and decrease in velocity. If you can get to a point where you can do this with every finger you are in a great place to apply it to the music you’re playing.

Other trilling conundrums

One of the things I found hardest when I began playing trills was keeping an awareness of the pulse while playing a trill which felt organic rather than metronomic. Sadly I don’t recall how I overcame this stumbling block, but using a metronome will certainly help. Having an audible beat to play against will help you keep track of the number of beats you’re trilling for and in time you’ll be able to maintain this sense of pulse in your head against even the most flexible and shapely of trills.

Keeping your upper notes on the beat

Because we perceive trills as requiring masses of speed, it’s easy to panic about fitting everything in. Somewhere in our subconscious, a small voice tells us that if we begin the trill earlier it’ll give us more time to get all those whizzy notes in. You can’t deny the logic, but sadly it just doesn’t work! The end result is a trill which may begin on the upper note but it often comes so early that by the time the chord with which it’s intended to clash (thus creating the desired feeling of tension) comes along, the upper note is but a distant memory!

Remember my advice earlier about spending more time on the appoggiatura and less on the wiggling notes. This may help, as the appoggiatura then becomes a more significant note in its own right. In fast pieces though this will often not be enough to cure your impatience to get trilling. To conquer this problem a good practice strategy is to play your piece of music, inserting only the appoggiaturas and leaving out all the wiggly notes. Really focus on getting them firmly on the beat. Then once you’re happy, add back in some twiddles, while maintaining the appoggiatura on the beat. Even after you’ve done this you may slip back into bad habits, so never be afraid to go back and repeat the exercise periodically.

Learn from others

To finish off, the most important piece of advice I can give you is to listen to lots of Baroque music. YouTube is a fantastic resource and there are lots of wonderful performances to be found by amazing recorder players. Do a search for names such as Dan Laurin, Erik Bosgraaf, Pamela Thorby, Frans Brüggen, Saskia Coolen or your favourite recorder professional and you’ll find no end of sonatas and concertos which contain a myriad of trills for you to enjoy and inwardly digest.

Here are a few suggestions to get you started:

Barsanti Sonata in C major:

Handel Sonata in D minor:

Mancini Sonata in A minor

Remember too that you don’t even need to restrict yourself to recorder music. The same principles apply to Baroque music played on any instrument so you’ll never be short of listening material. Really focus on how and where they play trills and gradually you’ll begin to understand where you could add them into your own performances.

If you have your own trill tips, perhaps shared with you by your own teacher, do share them in the comments below so we can all learn from each other.

Further reading

If you’d like to explore the topic of trills further I can recommend some books which you may find useful:

Johann Joachim Quantz - On Playing the Flute (1752) - Faber & Faber

A classic book, intended as a guide for flautists, but relevant to anyone who plays Baroque music. Available in paperback and eBook formats.

Gudrun Heyens - Advanced Recorder Technique, Volume 1 - Schott

A fantastic resource, packed with practical advice and exercises. Volume 1 is devoted to fingers and tongue, while volume 2 covers breathing and sound. Originally written in German and translated to English by Peter Bowman.

Walter van Hauwe - The Modern Recorder Player, Volume 2 - Schott

This three part series is a classic reference and practice book for the recorder. Volume 2 contains masses of exercises for honing your trills.